BijouBlog

Long Hair on Men: Dangerous and Powerful

Long hair … when I was growing up in a white Catholic suburb where moms stayed home, produced multitudes of children, and hung up sheets outside on clotheslines, in the late sixties and early seventies, long hair on men was considered almost evil, a symbol of danger and rebellion. You know, those dangerous hippies downtown with their sex and drugs and rock 'n roll.

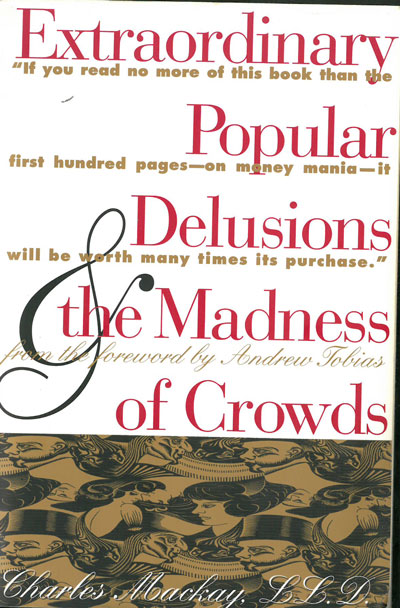

Now, according to one book written long ago in the nineteenth century, now incredibly relevant given the state of our nation, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, devotes a whole chapter to the influence of politics and religion on the hair and the beard.

St. Paul's dictum, meant to be only for local consumption and not a universal maxim, “that long hair was a shame unto a man,” was interpreted literally, especially in the days when church and state were not separate.

Even before the theocratic ideal of the Christendom, the powerful often dictated men's hair length. For example, Alexander the Great though that beards of his soldiers “afforded convenient handles” for an enemy to grab, as preparation for decapitation. Thus, he ordered everyone in his army to shave.

Yet, especially in the early Middle Ages (or Dark Ages), long hair was symbolic of royalty or sovereignty in Europe. In France, only the royal family could enjoy long, curled hair. Yet the nobles did not want to be viewed as inferior, imitated this style, and also added long beards. The great Charlemagne sported long hair and a beard, but after the ravages of the Vikings and the political and social chaos that ensured after Charlemagne's death, the nobles then kept their hair short. In contrast, the serfs kept their locks and beards long as perhaps a way of less than subtle defiance.

This flip-flop continued for centuries. Of course many famous churchmen, such as the famed St. Anselm of Canterbury, were virulently against long hair on men. King Henry I of England defied him by wearing ringlets. Much later in England, during the Civil War between the Roundheads (Puritans and Independents) and Cavaliers (Monarchists), hair became a dividing factor, and not just physically.

The Puritans though all manner of vice lurked in the long tresses of the monarchists (this long tresses later became wigs, and legal authorities in England still wear a variant of these wigs when hearing cases), while the monarchists accused the short-haired Puritans of intellectual and moral sterility. According to MacKay, “the more abundant the hair, the more scant the faith; and the balder the head, the more sincere the piety.” Well, I guess those short-haired macho muscular Christian Mormon missionary guys are closer to God, but then why is Jesus usually depicted with long hair?

Given the tendency toward fascism unfortunately evident as we approach the second decade of the 21st century, I hope no dictator decides, like the King of Bavaria, to ban moustaches, or more recently, that dreadful North Korean beast who ordered that men in his domain could only have their cut in a limited number of ways. The reasons for both these directives are obscure.

The fascination with hair clearly never loses its intensity. Women's hair has always been hidden or even eliminated in some patriarchal systems because of its association with sexual power; it's interesting to see that men's hair has also suffered restrictions as well for reasons associated with power dynamics. Whatever or however hair fashions change, let's face it, the hair styling and shaving supplies businesses will always benefit!

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

Comments