posted by guest blogger Miriam Webster

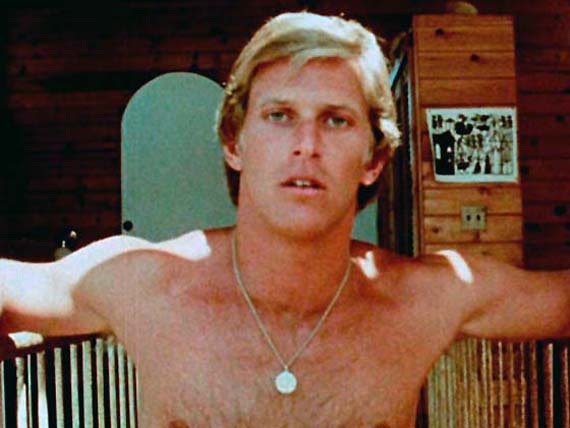

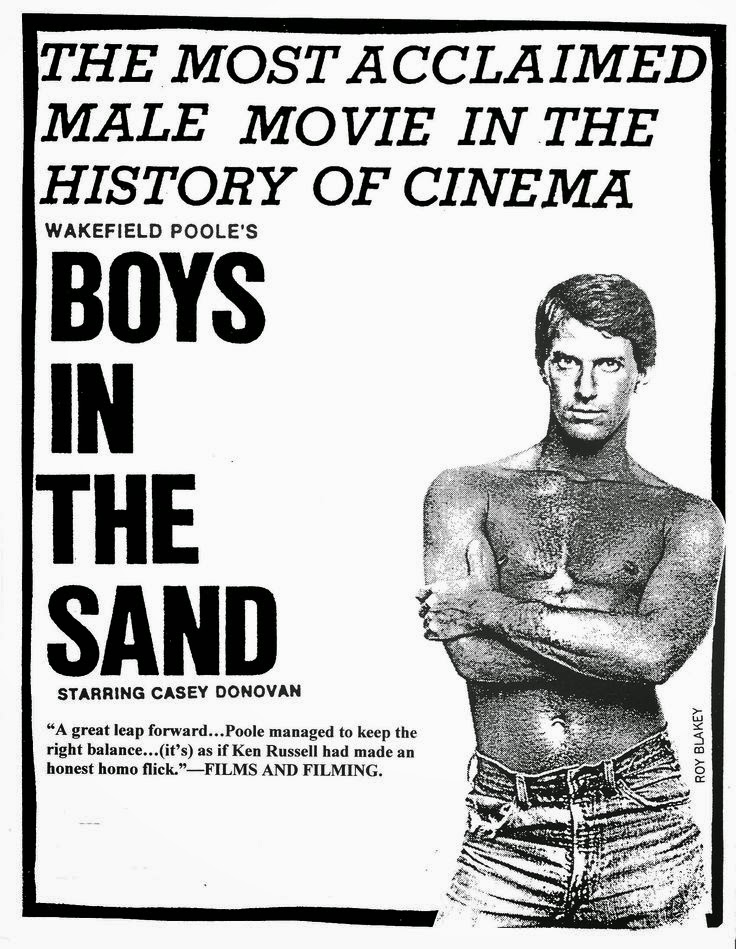

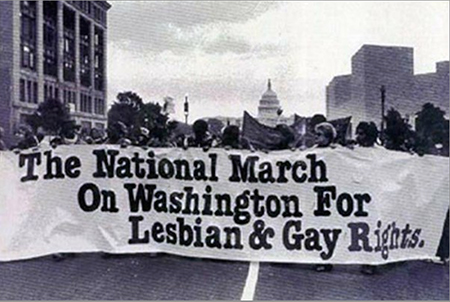

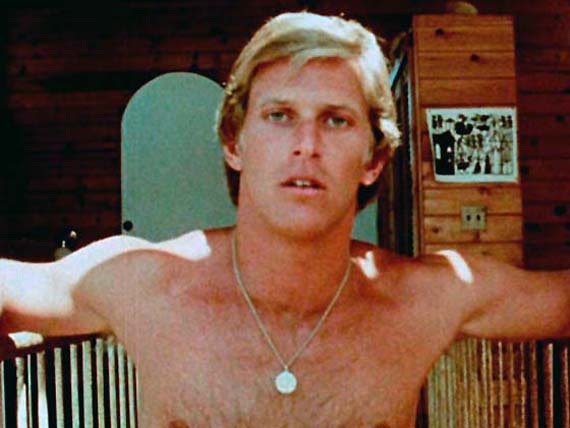

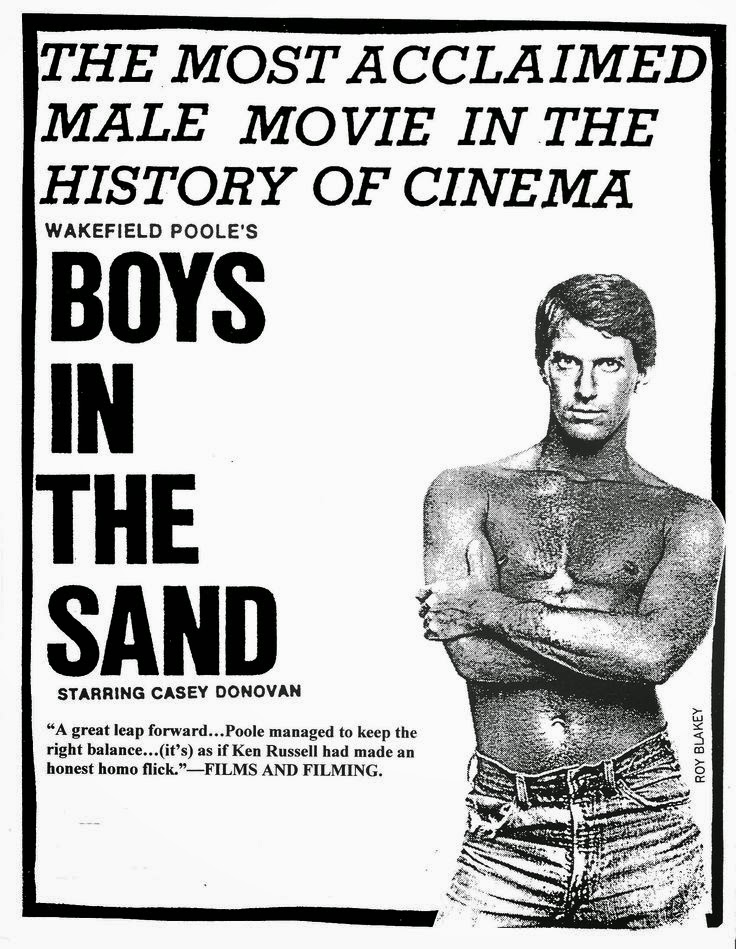

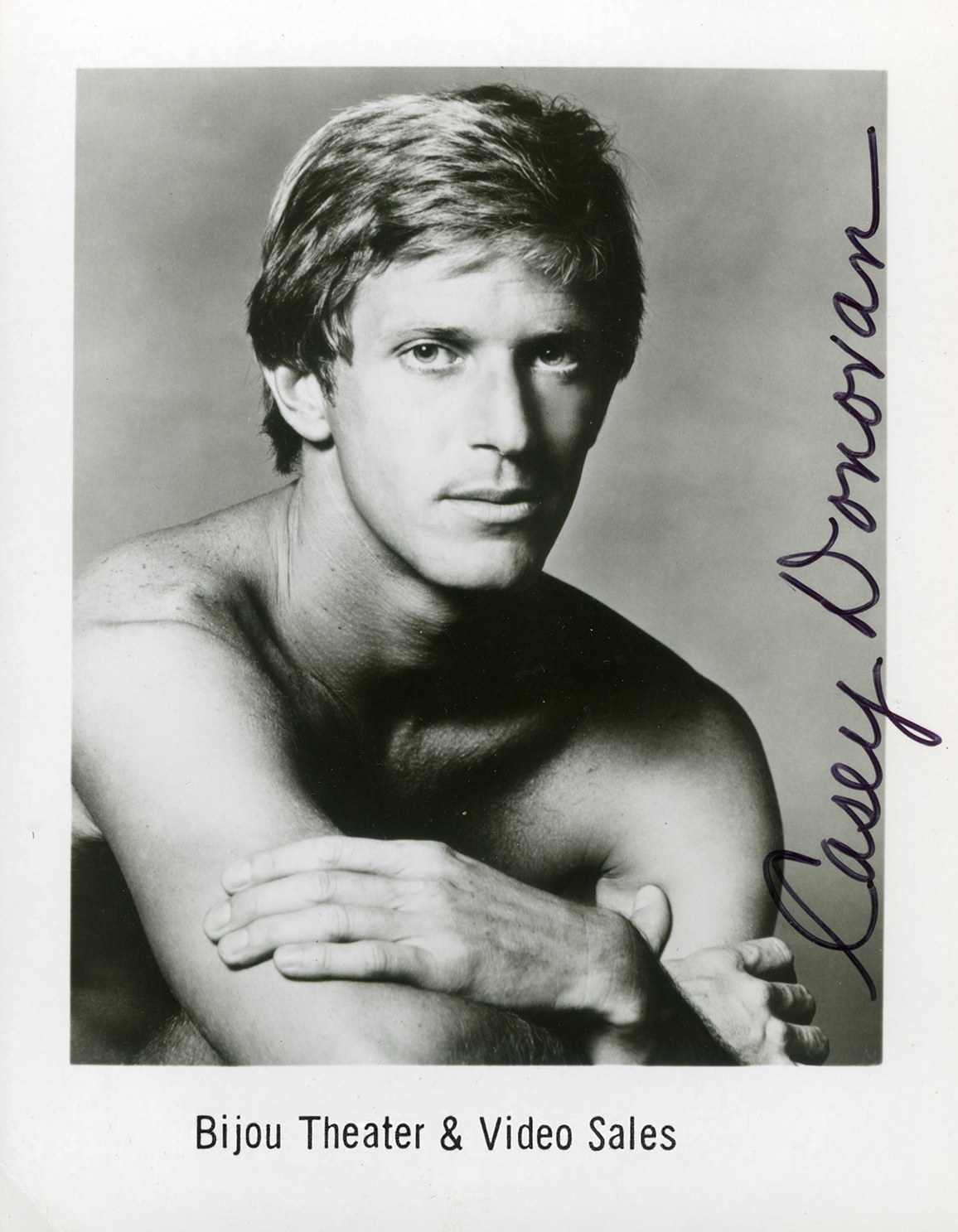

Casey Donovan, who became a legend after his lead performance in Wakefield Poole's Boys in the Sand, was easily the very first true gay porn star. Released in 1971, the film made its debut in the early days of gay liberation as well as the early days of hardcore (the era of “porno chic”), making a significant impact. It premiered at New York City's 55th Street Playhouse, which typically screened foreign and art house cinema, and was the first gay porn film to achieve crossover success, to garner considerable attention from the press, and to be reviewed by Variety, even making it onto their listing of the top fifty grossing films its opening week. The wild success of Boys rapidly helped to launch Casey, with his charm and glowing good looks, into underground fame and turn him into a gay icon. There was talk, at the time, that Casey might be the adult star who could fully break into mainstream film. Casey had aspirations of realizing this potential, and also of appearing in Broadway productions. He had been, and continued to be, involved in theater all his life, as an actor and as a lover of the medium.

Casey, born John Calvin Culver and typically known (and credited outside of his adult career) as Calvin Culver or Cal Culver, was raised in upstate New York. He did theater throughout high school and college, after being encouraged and mentored by his beloved high school English and drama teacher, Helen Van Fleet. (Roger Edmonson's biography Boy in the Sand: Casey Donovan, All-American Sex Star, source of the majority of this material, says he called her Auntie Mame, writing to her and sending her tickets to his plays throughout his life. “He took her backstage to meet Ingrid Bergman when he was in a play with the legendary actress. He took her to the Tony Awards, arranging for her to sit front and center in the audience.”)

When he eventually relocated to New York City in the late '60s, Cal made sure to attend as many plays as possible, from Broadway to small productions. He briefly moved to New Hampshire to do summer stock and joined the reputable Peterborough Players as an apprentice before returning to NYC, where he was chosen as a replacement for an actor in the off-Broadway play Pins and Needles. The success in 1968 of Mort Crowley's play The Boys in the Band, which directly focused on gay characters, paved the way for gay-themed plays. Cal was hired as an understudy in an early gay-themed play, And Puppy Dog Tails, in 1969. Around this time, Cal says (in a TV interview on Emerald City) that he was broke and searching for jobs in a paper and saw an ad hiring performers for non-hardcore roles in straight sex films. He wound up doing two "very strange little films" called Dr. X and Twin Beds, making $20 a day.

In 1970, he was cast in a raunchy low-budget thriller, Ginger (dubbed “a female James Bond”), with Cal in a role featuring some nudity. The film was critically panned, but Cal's performance received one of the few positive mentions: “Only Calvin Culver as the thrill-seeking jet set blackmailer shows any indication of better things to come.” Following Ginger, he was featured in a short run of the play Brave, following which he met Jerry Douglas. The two would go on to work together numerous times and in several capacities over the years. Douglas was directing a production of Circle in the Water, another gay-themed play, and brought Donovan on board. Douglas was impressed with how professional and charming Cal was, but commented that he was mysterious: “He always vanished promptly after each performance, not to be heard from until his next call.” Cal had a busy social life, was hustling and cruising after hours, and still making time to frequently see plays and operas.

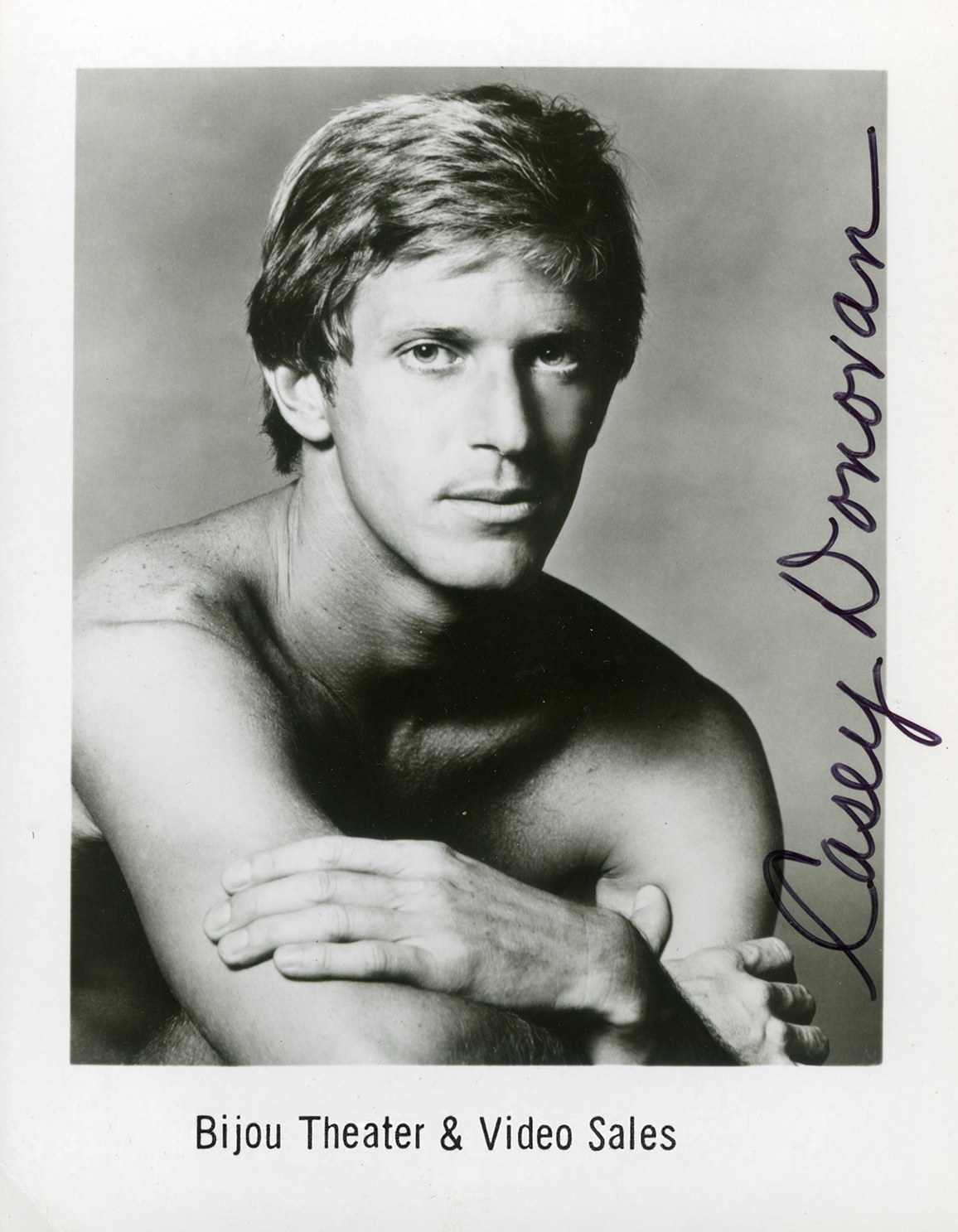

Just before Boys in the Sand, Cal broke into the hardcore porn world at age 28 when he starred in the 1971 film Casey, originally produced by Palm Features, later picked up by Hand in Hand Films, and currently distributed by Bijou Video. This film, though produced before Boys, wasn't substantially screened until after the release and success of Poole's landmark film. A co-star from one of the sex films Cal made in 1969 had a friend (Donald Crane) who was writing and directing a gay hardcore film and was looking to cast the lead. Cal needed cash and they were paying well, so he took the job. Though he described the shooting of Casey as uncomfortable because of its largely straight and tense crew and cast, Cal carries the film, attempting to create eroticism in the (mostly faked) sex scenes, exuding plentiful charm, and expertly delivering the film's clever and incisive dialogue, full of commentary on gay life in the era. Casey was well-reviewed when it did get distribution. Edmonson's biography says, “Aside from Cal's timelessly watchable good looks, there was his performance. It was a tour de force of its type... Cal not only plays the callow hero, but he also plays [in drag] the role of Wanda Uptight, his own fairy godmother... He played the role to the hilt without a trace of embarrassment, making it one of the more memorable star turns in the history of porn films.”

Images from Casey

Images from Casey

Casey is notable not only for being Cal's first hardcore porn – as well as one of the few films to properly make use of Cal's acting chops – but also, significantly, for giving him his pseudonym and alter ego. As he was modeling for a “legitimate agency” at the time and acting, Cal took the name Ken Donovan for his credit in this film, modifying it to Casey Donovan for his later porn appearances.

Because of Casey, Cal received a call from a friend who knew someone - a former dancer, theater director, and choreographer - who was making "some experimental movies" on Fire Island. This was Wakefield Poole. Cal met with him, saw some of what he'd been shooting, and agreed to take part in this beautifully photographed porn film, which was ultimately to become the classic, Boys in the Sand, that would transform Cal/Casey's life. He received glowing reviews of his performance and his image in the film and there was talk all over New York City (and, eventually, across the nation) about him.

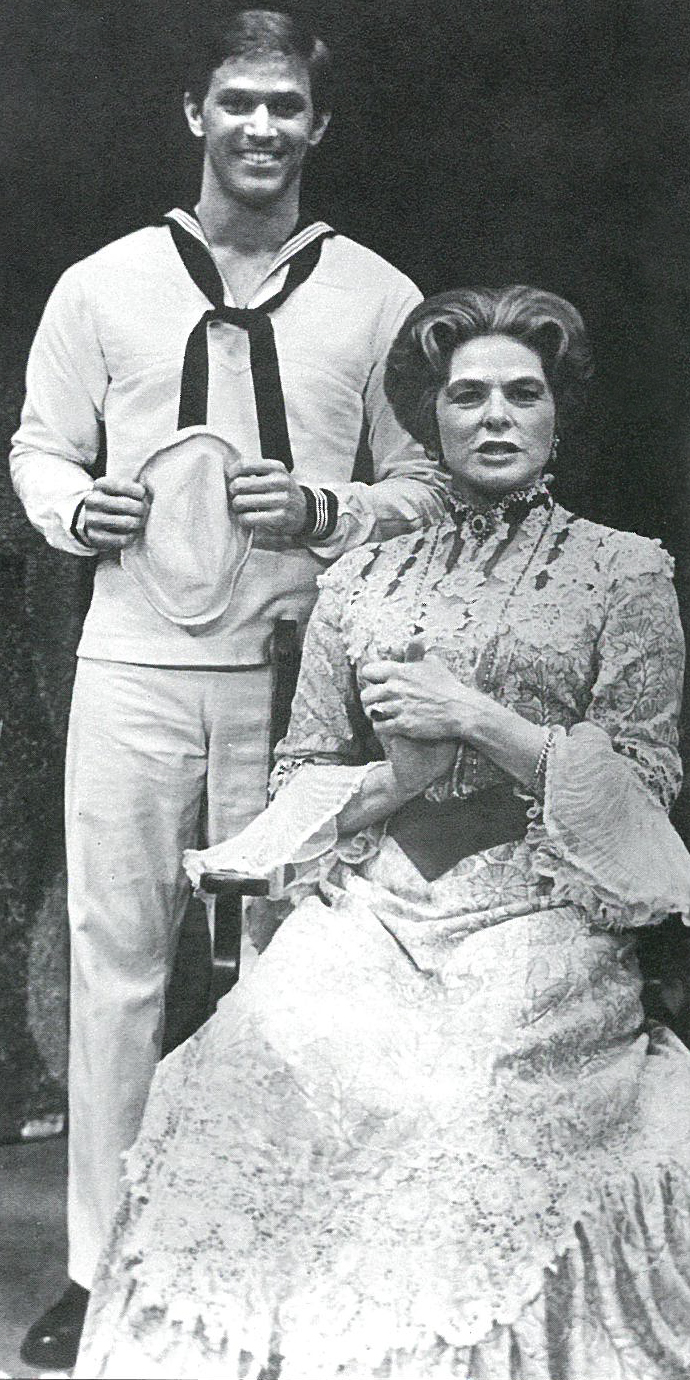

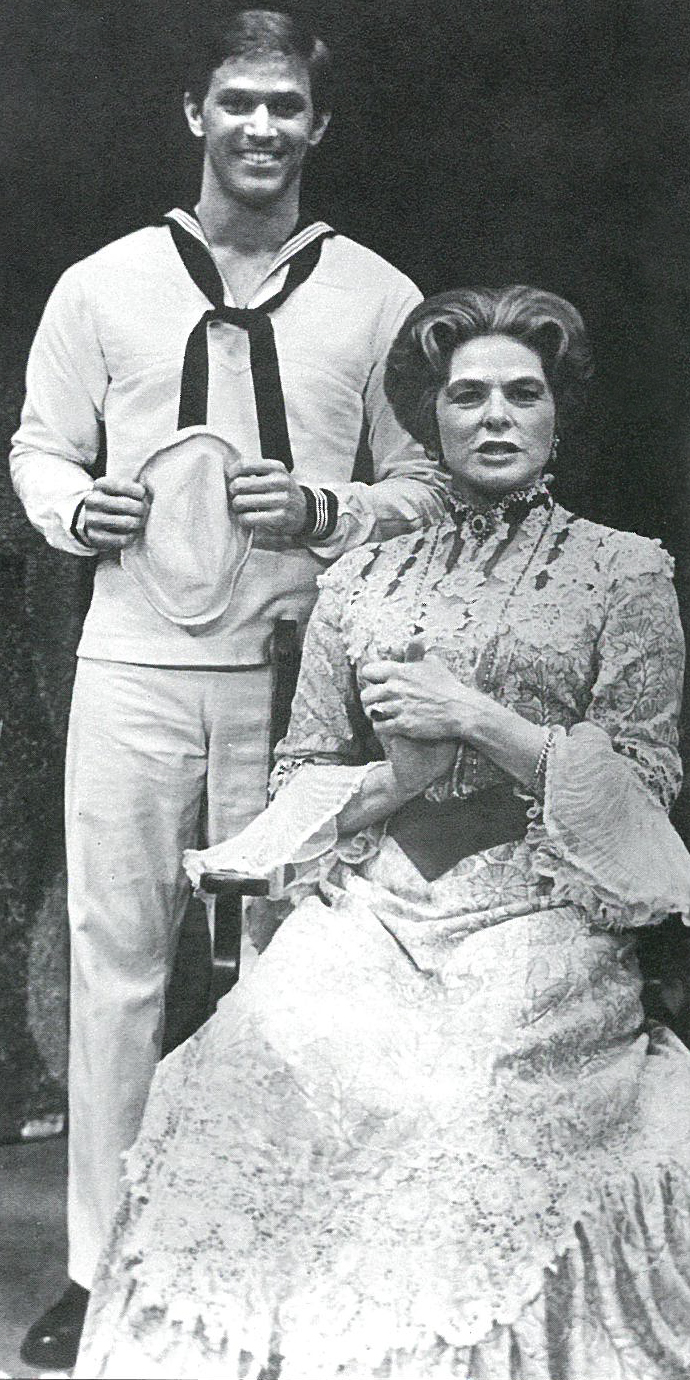

In 1972, Cal was cast in a small part in the George Bernard Shaw play Captain Brassbound's Conversion starring Ingrid Bergman, who described Cal as “having the same kind and as much charisma as Robert Redford.” A photograph of them together during this production became one of Cal's prized possessions and he said he learned a great deal from getting to watch Bergman act.

Cal with Ingrid Bergman

Jerry Douglas, his Circle in the Water stage director, contacted Cal about appearing in his porn directorial effort The Back Row (1972) co-starring George Payne. In Douglas' Manshots article “The Legend of Casey Donovan” in April of 1992, Douglas, who worked with Cal multiple times in both theater and porn productions, describes how Cal “approached stage and film work in much the same way. He began by creating the character... and by studying the script, even on porn films. Rehearsals and shoots were always filled with his laughter, easy and laid back, even in the middle of an intense sex scene. But performing or filming was always a job to him, and a job he took very seriously.”

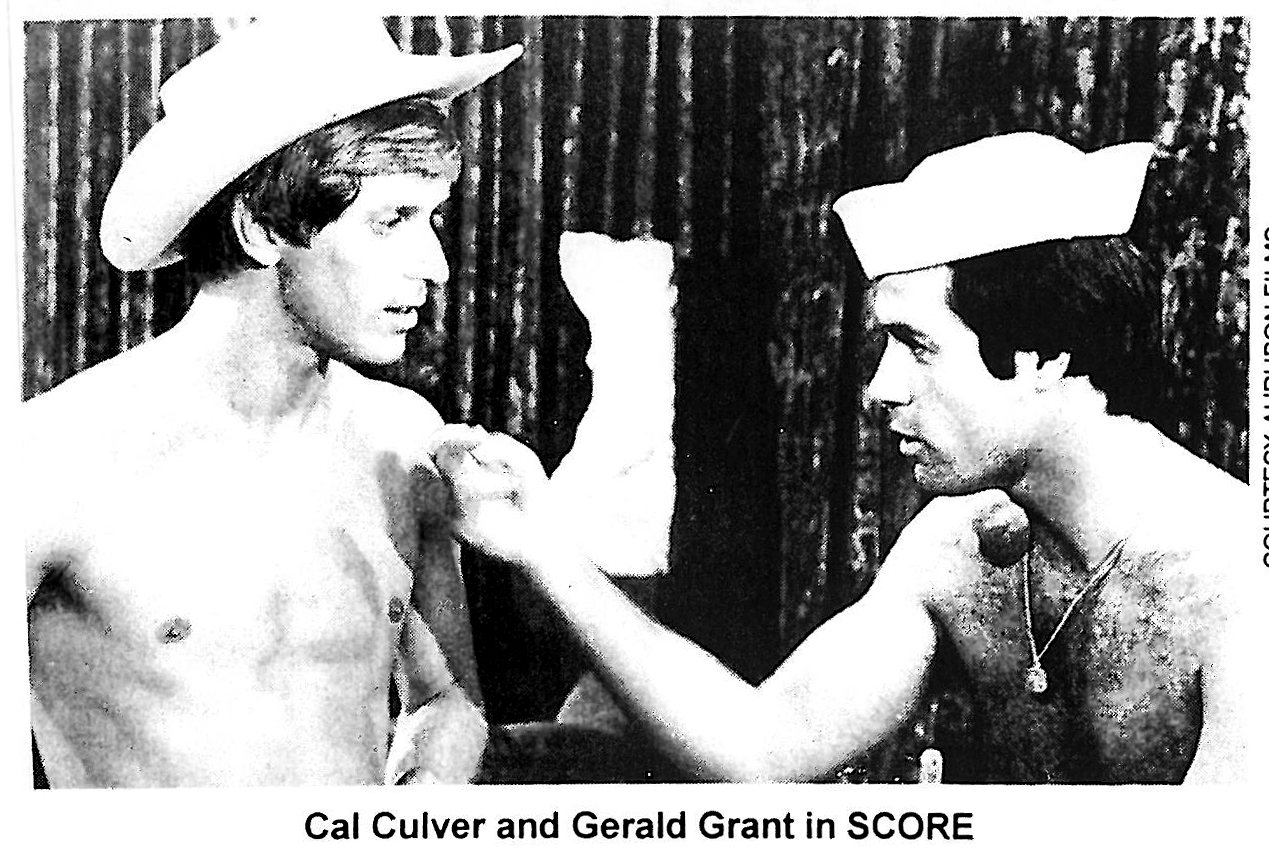

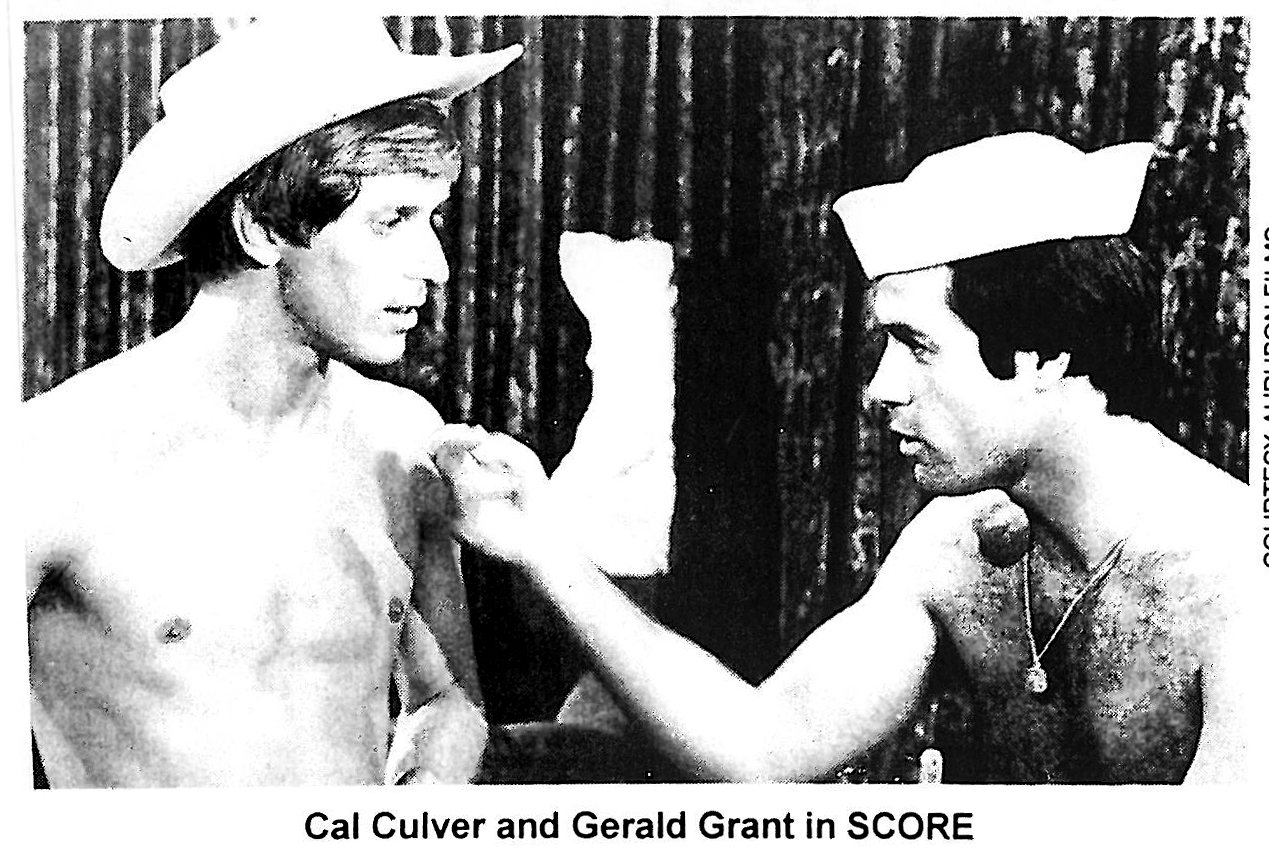

Shortly thereafter, Douglas was adapting his swinger play, Score, for the screen and Cal was cast. The film – a talky and very entertaining, nearly-hardcore softcore bisexual film – was made by notable director Radley Metzger. Metzger had come from straight and lesbian softcore films and was soon to move into glossy straight hardcore films (including one of his more well-known works, 1976's The Opening of Misty Beethoven, which would feature Cal in a small role). The sex scenes between Cal and co-star Gerald Grant are the most explicit and erotic in the film, the chemistry and tension between the two palpable, and Cal – here, as in Casey – deftly handles a significant amount of dialogue and delivers a compelling, nuanced performance.

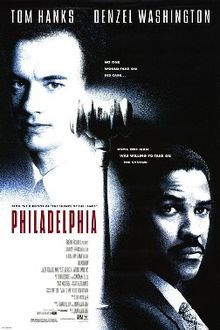

In the following few years, Cal appeared in a handful of small non-porn film parts and met with a number of producers in mainstream film about potential large-scale projects. Stage and screen co-star Michale Kearns said, “He was really, seriously talked about as potentially crossing that invisible line into the mainstream world of Hollywood films. His acting was immaterial. He was a star. He had that ineffable quality...” A Variety article said Cal could be “the bridge from hardcore to legitimate features” and Cal believed he could make that transition. His friend and then-roommate, Jake Getty, says, “He really didn't see – and I honor him for it – the difference between the two mediums. To him it was all an expression of theater... There was a great deal of legitimate theater with nudity and sex, implied sex in any case. Cal felt that there was no difference, that it was just a matter of how you perceived it. For him it was all a matter of the expression of emotion. He saw no difference between the nudity in Hair and the nudity and sex in Boys in the Sand.” But Cal's Hollywood roles never quite manifested.

In 1973, Cal played a series of small parts in a Lincoln Center production of The Merchant of Venice starring Rosemary Harris and Christopher Walken. One of his roles was as Jesus Christ, wearing only a crown of thorns and a g-string and carrying an 8-foot cross. This production featured, also in small parts, Robert Tourneaux of the theater and film versions of Boys in the Band. Tourneaux was in a similar predicament to Cal, even without a porn career – his notoriety as a gay actor and from a well-known gay role was putting a stop to his film career.

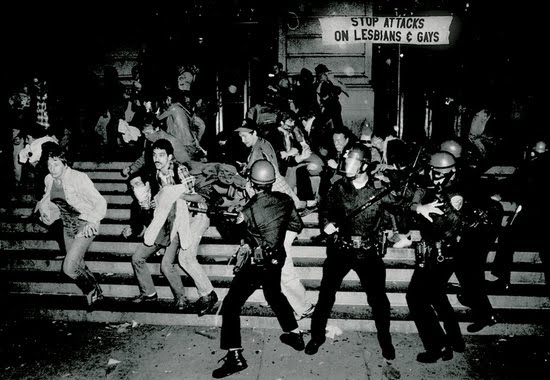

As Cal was beginning to realize, the dual stigmas against porn and out gay actors were preventing his Hollywood aspirations from manifesting. Wakefield Poole said he also experienced this inability to move into mainstream film directing because of his porn work: “The legit film line couldn't be crossed. They would exploit you, but they didn't dare let you do a legitimate movie. The ugly truth was that there was no crossing over. None at all.” (Correction: There were some exceptions; gay porn director Tom DeSimone successfully crossed over into mainstream film/television directing. See our recent interviews with him about his career.)

Cal, in a 1983 Men in Film interview, said “Perhaps I was naive but it was a rude awakening for me to find out that Hollywood is one of the most closeted and hypocritical cultural centers in the world. I learned that an openly gay actor like myself was not welcome to gay directors and producers who believe it is essential to keep their sexuality a secret. Once an actor has made a porn movie, it is very difficult to 'cross over'. And it all has nothing to do with how much talent one has. It is all about how an actor is perceived and prejudged. In a limited sphere, my films made me famous, but in another sense, they were a handicap. I tried to maintain separate names and identities at first... It got increasingly confusing... Besides, the secret could not be perpetuated endlessly.”

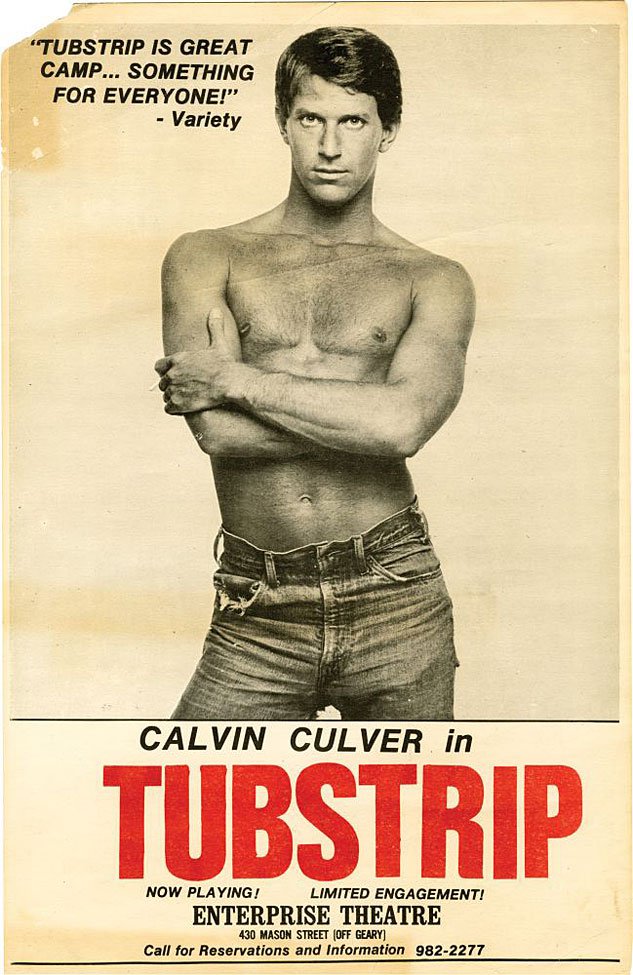

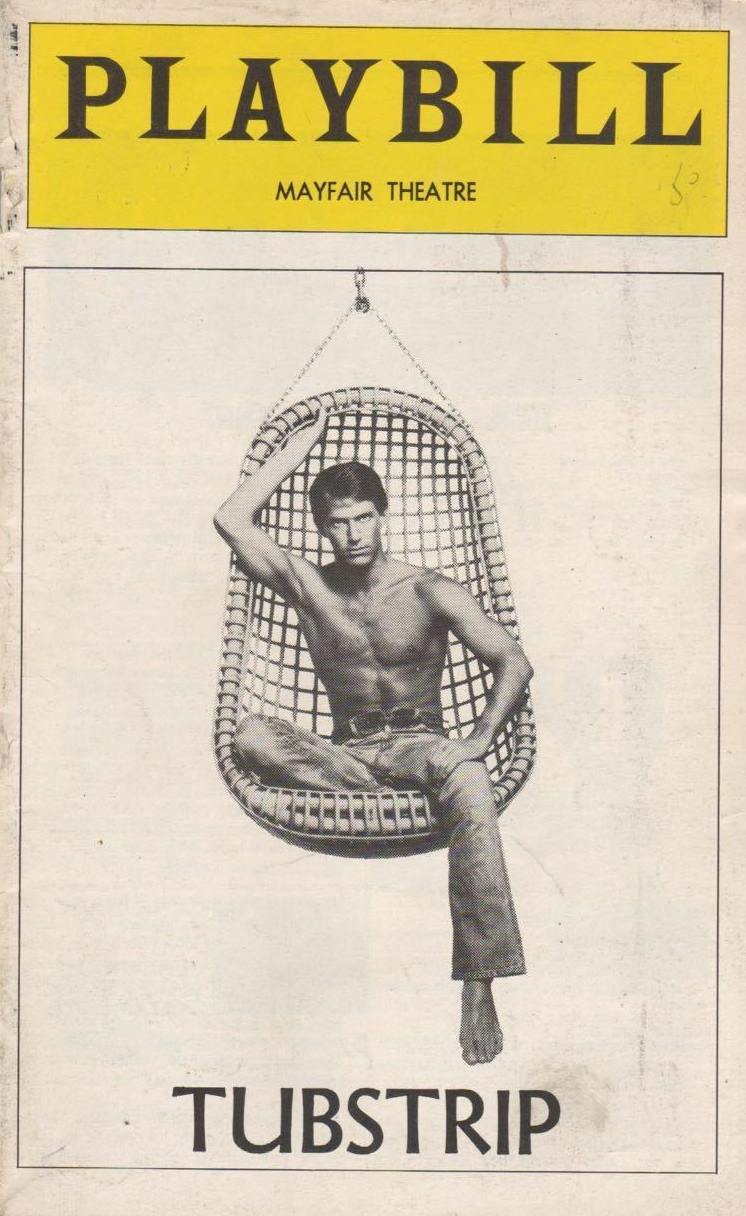

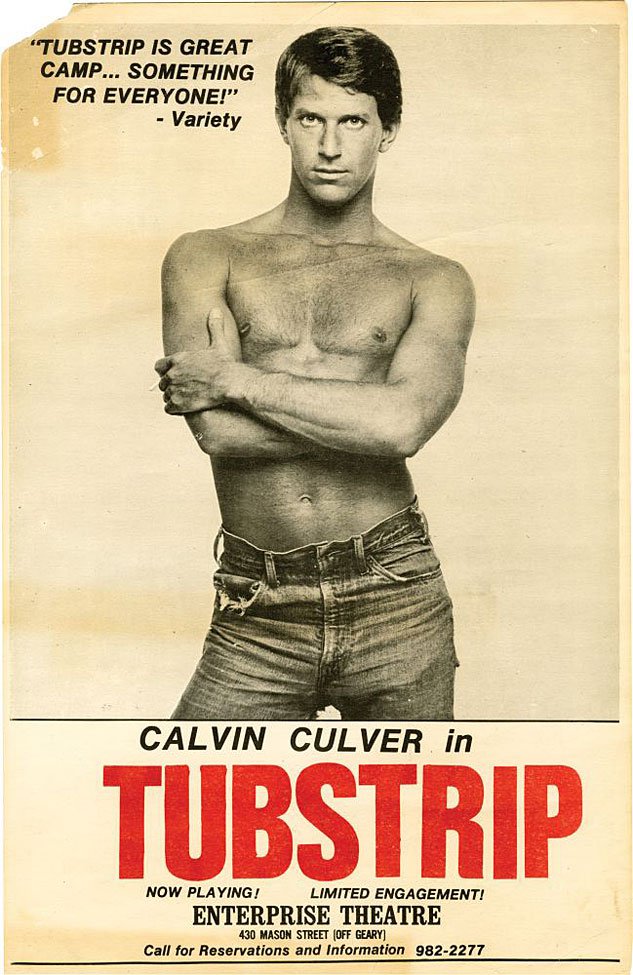

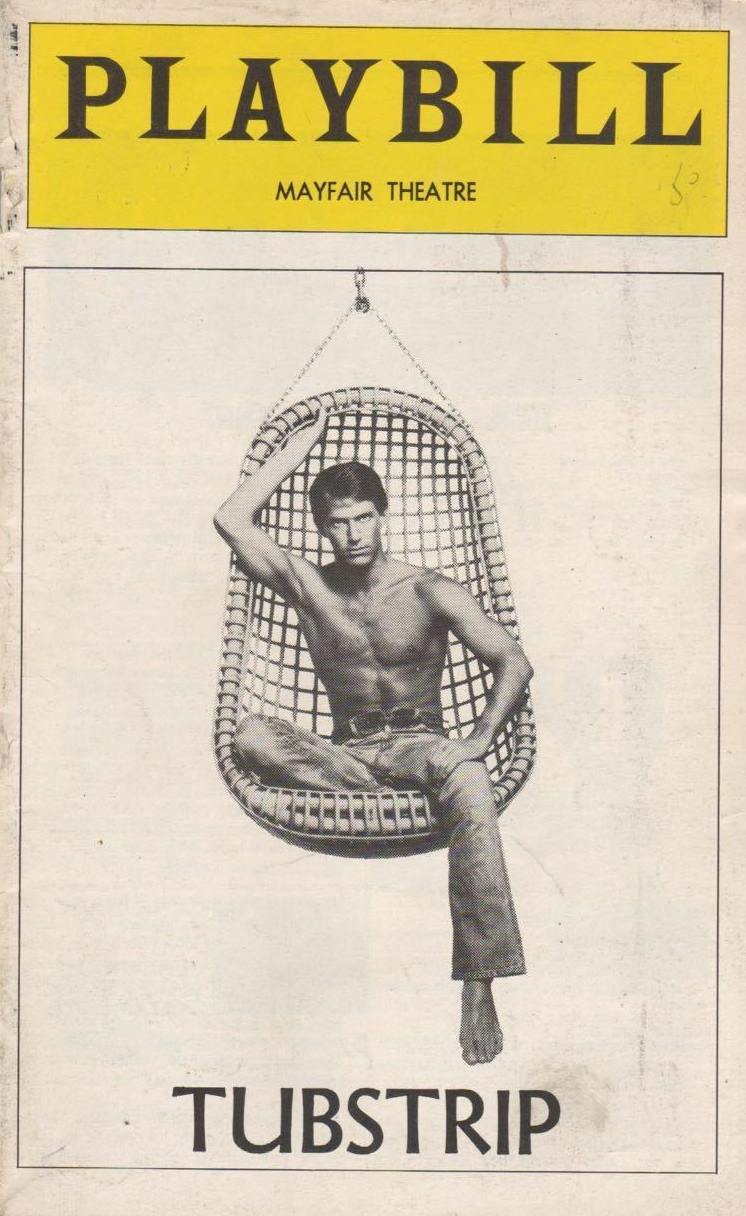

Cal gave up his Hollywood hopes eventually, but continued to perform in porn and in theater. He was dropped from a production of Frederick Combs' play The Children's Mass, in which he was to co-star with Sal Mineo (also a friend of Hand in Hand Films heads Jack Deveau and Robert Alvarez), but he worked with Jerry Douglas once more in 1974 in his bathhouse play Tubstrip, also starring Score's Gerald Grant and a fellow early porn star, Jim Cassidy.

Cal was the biggest attraction and the play had a long run in New York, then runs in L.A. and San Francisco, and Cal performed in it to the end. Fans were excited to see Casey Donovan live and Cal “made time to meet with fans who gathered at the stage door every night after the performance.” During this era, he would reportedly screen his porn films for his theater cast-mates at after parties (Boys in the Sand for the Merchant of Venice cast and Poole's 1974 film Moving, co-starring Val Martin, for the Tubstrip cast). Michael Kearns commented on one of these viewings: “He acted like it was Gone with the Wind. He really behaved like a star – not temperamental but like a real star. He didn't feel a bit of shame about what he did on the screen. Even when he was getting fisted, there was a certain elegance about him. He had incredible aplomb.”

Between porn and theater gigs, Cal continued to work as an escort, periodically served as a gay celebrity tour guide on international trips (including to Italy, Egypt, China, and Peru), and did a stint running a bed and breakfast (“Casa Donovan”) in Key West. In his porn career, he worked with with major directors, stars, and studios, including Falcon (The Other Side of Aspen, 1978, co-starring Al Parker and Dick Fisk), the Gage brothers (L.A. Tool & Die, 1979, and Heatstroke, 1982), Christopher Rage (Sleaze, 1982), Poole again (Hot Shots aka Always Ready, 1982, and Split Image, 1984) and Steve Scott (Non-Stop, 1984), and he performed in the 1985 safe sex films Inevitable Love (with Jon King) and Chance of a Lifetime.

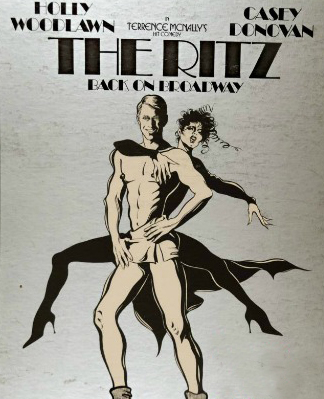

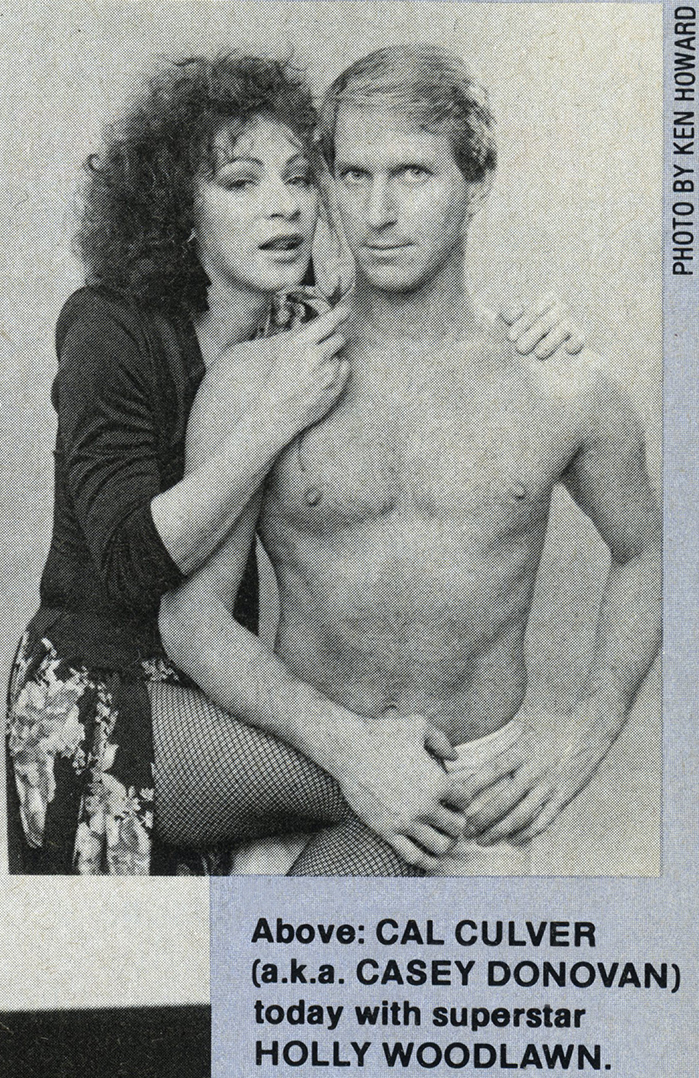

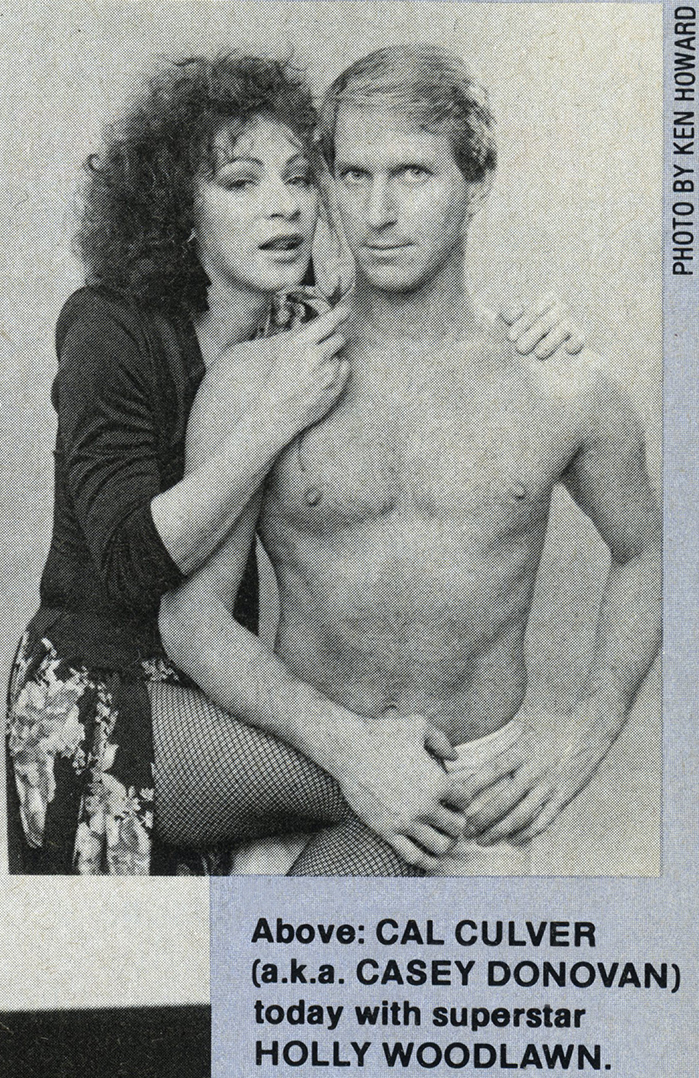

After a break from the stage and from New York City, Cal planned a return with a 1983 off-Broadway revival of the Terrence McNally play The Ritz. The play, which originally ran on Broadway in 1975 starring Rita Moreno, Jerry Stiller, Jack Weston, Kaye Ballard, and F. Murray Abraham, was based on Bette Midler's rise to fame at The Continental Baths in the early '70s. (An additional connection to Cal: McNally originally called the play The Tubs, but when it was to be produced on Broadway, its name had to be changed because it was too similar to that of Douglas' Tubstrip.) Cal was brought onto the play's revival as a co-producer, as well as a star, and helped to finance it. Cal played detective character Michael Brick, who spoke in a falsetto voice throughout, and Warhol superstar Holly Woodlawn was cast in Moreno's leading role. The revival wound up a critical and financial disaster, the director receiving the largest amount of backlash, and only ran one night. Woodlawn said, while that performance was a mess, “Everyone panicked too soon. The opening night was a horror, but if given a chance, things would have settled in and worked out... We just needed more time to make it work.”

After this disappointment and its financial impact, Cal returned to Florida and was never to appear on stage in New York again. However, he couldn't give up on theater and – when not away traveling – attended and began acting in community theater productions in Key West. There, he was in a production of The Prime of Miss Jean Broadie and in William H. Hoffman's pioneering play about AIDS, As Is.

Woodlawn called Cal “the most gracious man I've ever encountered.” His friends remarked upon how dedicated he was to his fans and, while an enigma and a mass of contradictions, how sensitively he received the people he interacted with – strangers, fans, clients, co-workers, lovers, friends. Douglas' Manshots article says Cal “knew that he was a pioneer, a role model, and a superstar with obligations to his public. And so, he took great pains always to appear in public well-groomed and sober. He charmed his fans in every public appearance by listening, again and again, to their personal tales as if each of them were his closest friend. He corresponded with many, sent out hundreds (maybe thousands) of photographs at his own expense, and was never in too much of a hurry to sign one more autograph.” Bijou owner Steven Toushin similarly recalls Cal's appearance at the Bijou Theater. He was booked there to promote a film, dance on stage, and to meet fans and sign autographs. He says Cal had a great time interacting with the customers and stayed hours beyond the time he was scheduled and paid for, enjoying having conversations with his fans.

Cal's hardcore and softcore films serve to immortalize his charm and his talent, as both an actor and a sexual performer. Though his porn roles modified his acting career, in a Men in Film interview, Cal said, “I enjoyed the idea that I was doing something that very few people had ever done... My life was made much more exciting by having done those films... I did plays, I was on magazine covers, in national fashion ads... I think porno worked in my life because I was so honest about it... Once I realized that my appearance in gay films was held against me in some quarters, I decided to put sex to even greater use – not less – in augmenting my income. We live in a society with deeply rooted feelings of guilt and shame about sex of any kind. If somebody makes a porn film, they are automatically beyond the pale. If somebody hustles, there must be something wrong with him. Maybe for some, not for me. I'm the living proof that it doesn't have to be that way. I'm still pretty much 'the boy next door' that I always was... I think my greatest accomplishment so far is something that doesn't show up in lights or get reviewed – and that's simply the sexual sanity that I have tried to contribute to over the past twenty years... I've tried to be honest, kind, and understanding with as many different people as possible, and I think that's much more important than just being gay.”

Cal's friend Jay McKenna wrote in a memorial article in The Advocate, “To myself and other young boys who were coming out in the early '70s, Cal Culver was a gay Adam – the first widely embraced gay symbol to appear during the post-Stonewall years. Back in 1971, when Cal's first film, Casey... was released, the gay movement was just beginning to amass some collective energy and wider acceptance, but gay existence was still underground and closeted. Coming out was a heartfelt and courageous choice. It was a calculated professional and social risk. So to teen-age boys like myself who were struggling to come to terms with it, Cal's spectacular emergence as Casey Donovan, unapologetic star of gay films, bordered on the heroic... My memory of him isn't obscured by false nostalgia. Cal had star power. He celebrated his gayness. He made me and others proud to be gay, so contagious was his spirit. Of course, like any human being, he had good days and bad days. But to be in his presence was to breathe a rarefied atmosphere.”

In 1985, two years before his death of AIDS-related complications, Cal returned to his home town to help his beloved drama teacher, Helen Van Fleet, celebrate her retirement. He visited with old high school classmates who all knew about his career in “the legitimate theater” and some about his porn career. Cal wanted to play a big part in Mrs. Van Fleet's celebration. Her daughter said, “it was really wonderful. He had written a parody of the title song from the musical Mame, and he sang it to her. It was an account of all the things they had experienced together over the years. It meant the world to her” and it received a huge ovation.

Sources:

Roger Edmonson, Boy in the Sand: Casey Donovan, All-American Sex Star

Jerry Douglas, “The Legend of Casey Donovan,” Manshots, April 1992

Jay McKenna, “Casey Donovan: To an Idol Dying Young,” The Advocate, October 27, 1987

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Casey_Donovan_(actor)

https://newyorkcityinthewitofaneye.com/2013/05/20/mondays-on-memory-lane-1981-one-night-only-at-the-ritz-with-holly-woodlawn-2013/

Emerald City TV #47, Wakefield Poole & Cal Culver

Join our Email List

Join our Email List Like Us on Facebook

Like Us on Facebook Instagram

Instagram Youtube

Youtube Follow Us on Twitter

Follow Us on Twitter Follow us on Pinterest

Follow us on Pinterest