By Madam Bubby

Usually a “mad scene” specifically refers to a particular scene from an opera written by bel canto composers of the early 19th century, such as Donizetti and Bellini. A soprano, usually suffering from a romantic love crisis, goes insane, and expresses her insanity, paradoxically, in difficult, complicated coloratura passages that require great vocal control.

The most famous occurs in the opera Lucia di Lammermoor. Lucia, in love with the family enemy Edgardo, is forced to marry someone her brother chooses, Arturo. Lucia kills Arturo on her wedding night. I grew up hearing the gay icon Maria Callas singing this scene on record, and I was mesmerized that she was able to invest the scene with such drama and a dark, complex timbre. Here was no Snow White singing tra la la to the birds. But, interestingly enough, the opera does not end with the mad scene. Lucia dies offstage, and her lover, Edgardo, kills himself. He actually gets a kind of tenor mad scene. But it’s generally the ladies who go mad, which reflects quite blatantly the misogynistic Victorian view that women, the "weaker sex," were more prone to mental disturbance: potential hysterics.

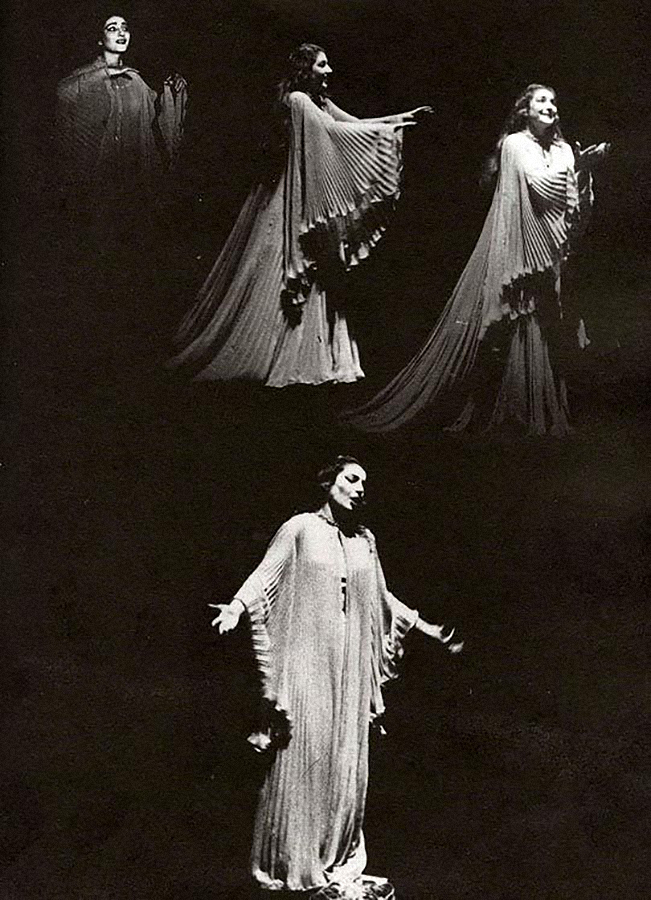

Callas as Lucia

The mad scene by the middle of the last century started moving to the end of movies, crystallizing to some extent in the grand dame guignol movies of the late 1960s and early 1970s. The end of Sunset Boulevard, the famous “I’m ready for my close up, Mr. DeMille,” scene of Norma Desmond, deconstructs the mad scenes of operas, because she thinks she is playing the necrophiliac Salome. One even hears a bit of music from the Strauss opera as she descends the staircase (that prop usually occurs in Lucia mad scenes). In fact, by the time Strauss wrote his opera Salome, one could even say the female protagonists of many operas written by that time were mad for the entire opera (or most of the time).

Norma Desmond at the end of Sunset Boulevard

Thus, Baby Jane Hudson in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? dancing on the beach with ice cream cones and others of her ilk come out of a rich tradition. The director Robert Aldrich really seemed to build his grande dame guignol films toward a final mad scene for the female protagonist, though in his underrated Autumn Leaves shows a male, played by Cliff Robertson, going mad, and he gets several scenes, but the most terrifying one occurs at about midpoint.

But it is also a scene of horrifying domestic violence (he throws a typewriter at his wife, played by Joan Crawford, after slapping her around). Like Edgardo in Lucia, he accuses her of treachery, but she is innocent. In reality, his father slept with his now former wife (she a willing accomplice), and discovering them together precipitated his descent into what, based on the movie, is paranoid schizophrenia.

Joan Crawford and Cliff Robertson in Autumn Leaves

Aldrich created another mad scene in The Killing of Sister George, a groundbreaking LGBTQ movie on so many levels, not only for its filming a scene in an actual lesbian bar, but, for the fact that the protagonist, June Buckridge played by Beryl Reid (known as George because of the character she plays in a soap opera, Sister George, a jovial country nurse in an English village) is out and proud as a lesbian. Many critics today tend to place this move in the “self-hating” LGBTQ subgrenre. Yes, George is certainly not the most stable person. She yells a lot, drinks a lot, and certainly, which one could argue isn’t really a character flaw in some of the situations she encounters, shows no compunction about telling some persons off in not the most dainty language.

Her relationship with Alice does not strike one as being the healthiest by today’s standards. I remember watching the scene where George, always jealous, punishes Alice for a supposed flirting (with a man) by making her kneel before her and eat her cigar. For the mid 1960s, this scene was risqué, and I perceived that perhaps there was some element of BDSM play involved, but it also seems to be moving into the realm of emotional abuse. And it’s not Alice as the victim of the “bull dyke” George. Alice is blatantly egging her on, and by pretending to enjoy eating the cigar; yes, she does take back control of the dynamic, knowing she is hurting George by, as George both yells and cries, “ruining” it.

Thus, one can see the characters aren’t camp caricatures. The character George plays gets killed off in the series (hence the title), and the fate of her career and relationship gets wound up in the machinations of the cliched reptilian predatory lesbian, played by Coral Browne.

Spoiler alert: she loses her job and her lover; the Coral Browne character in a scene of underhanded viciousness at George’s farewell party at the television studio suggests she get a job playing the voice of a cow in an animated puppets series for children. A gut-wrenching scene occurs when Alice leaves her. Reid masterfully plays it as both horribly hurt and horribly angry together, the emotion much like that of another spurned operatic character, Santuzza in Cavalleria Rusticana (from the time of whole “mad operas”). Shortly thereafter, George enters the empty studio, smashes the camera equipment, and beings mooing like a cow. She is wordless. No romantic words, no ecstatic high notes like Lucia sings, no cameras for a Norma Desmond close-up.

Beryl Reid as George in The Killing of Sister George

But, is she really mad? Does she really enter another reality like Lucia and Norma Desmond and Baby Jane? She’s not fantasizing about a marriage that never took place, and she’s not retreating into memories of a forever lost stardom. It seems she’s justifiably enraged, but also, given her indomitable character, understanding that she will do that job. She knows she has lost. She knows it’s degrading.

And like many LGBTQ persons, she knows who she is, and because she knows, she can choose, or at least to try and choose, what happens in her life. What’s sad is that she feels like she can only choose her losses. I just wonder if she’s really at the same level of victimization and its sister, in those cases, madness as the Romantic heroines of opera or the characters like Baby Jane who are both torturer and victim in grande dame guignol cinema.

Similarly, the complex dynamic where the madness, or appearance of madness, exists perhaps to crystallize at the highest level of tension the torturer/victim binary appears in a classic gay porn movie, Drive, directed by Jack Deveau (which Bijou carries on DVD and Streaming). The mad lead character/anti-hero Arachne plots to kidnap a scientist and eliminate everyone’s sex drive.

Christopher Rage as Arachne in Hand in Hand Films' Drive (1974)

Arachne (played by legendary director Christopher Rage, here billed as Mary Jim Sstunning, in a script written by Rage) certainly camps it up as she attempts to set her diabolical plot in motion. But the movie unveils at the end how the one who desires to castrate is actually ferociously repressing her own sexuality. She is last seen in a dungeon with the men she had imprisoned. Secret agent Clark liberates the prisoners, and Arachne is left alone. But this whole mad porn opera contains a moment of somber lucidity. Arachne holds a glass bottle with a severed penis. She knows she is forever trapped in a cycle of endless desire like a spider in a web, consuming its mates but never satiated:

“I hunted at night until it wasn’t enough to hunt only at night, and then I hunted during the day too. I couldn’t stop. I didn’t want to stop. My thoughts were only of hard bodies, rigid with the desire for me — beautiful men swollen with the need for me. They were all around me and I chose the ones who looked most eager.

“Until I saw a man who was so perfect, with a hunger in his eyes that reflected my own hunger — and I knew he was the one. I knew we could feed from each other, claw at each other with a need we didn’t care to understand.

“Drugged with desire for each other’s hot naked skin, tense muscles pushing — and then filling me with his need, white and hot. Crushing me with his strong arms, pressing down on me and into me, until I closed my eyes with the ecstasy and perfection of him, and I screamed for him — and I screamed for me.

“And I opened my eyes and I was alone.

“And I vowed then that I would bring an end to it all. Man would have to search no more: Arachne would be the answer.”

She knows. She knows who she is, ultimately more frightening than the mad scene at the end, which usually ends in the liberation of death.

Join our Email List

Join our Email List Like Us on Facebook

Like Us on Facebook Instagram

Instagram Youtube

Youtube Follow Us on Twitter

Follow Us on Twitter Follow us on Pinterest

Follow us on Pinterest