In 2019, Robert Alvarez, co-founder and editor of the groundbreaking and influential early gay porn studio and distribution company, Hand in Hand Films, kindly took the time to do a phone interview with Bijou.

Along with his partner Jack Deveau, as well as Jaap Penraat, and, later, Kees Chapman, Alvarez co-founded and was at the helm of Hand in Hand Films. Formed in 1972, a mere few years after more permissive legislation in the U.S. began allowing for the exhibition of hardcore films, the studio undertook ambitious and elaborate cinematic productions, expanding the ideas of what a pornographic film could be, and constructing their ideas into a large catalog of outstanding and entertaining narrative features. They additionally became an early distributor of the work of a number of other gay adult filmmakers, as well as their own product. A highly collaborative enterprise, Hand in Hand's films combine the creative influences of all of their participants. They continued making films until 1982 and distributing until 1988.

Alvarez, a skilled editor with a background in dance and experimental and documentary film, elevated Hand in Hand's output with his technical polish and creative flair, helping to create the distinct style and high quality level of the studio's output. From character dramas, to comedies, to outrageous psychedelic and horror films, his work on Hand in Hand's productions covered a range of tones and genres, but maintained Hand in Hand's cinematic quality and particular sensibility. With some of the studio's wilder and more avant-garde films and sequences, Bob applied complex and experimental editing and post-production effects, leading critics to frequently praise the “Alvarez effects” that enhanced scenes and often created some of the movies' best moments.

In the conversation that follows, Bob discusses his artistic background and influences, Hand in Hand's formation, his relationship with Jack Deveau, his editing style, the studio's philosophy, and more.

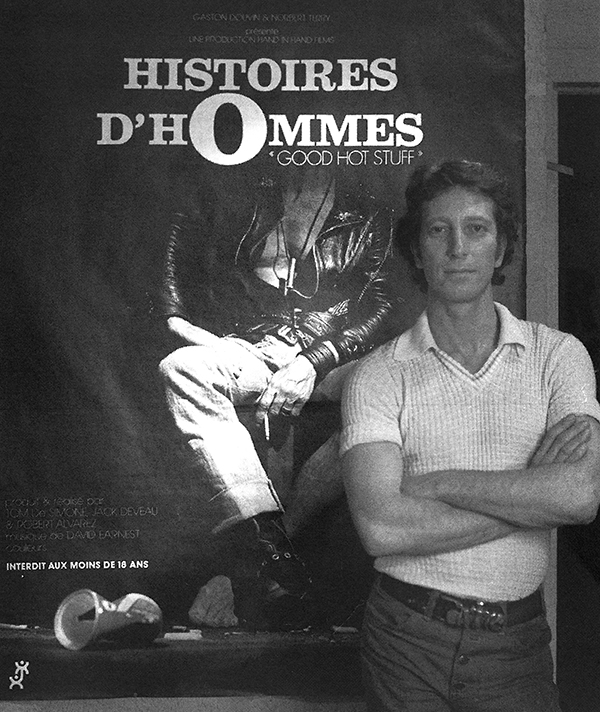

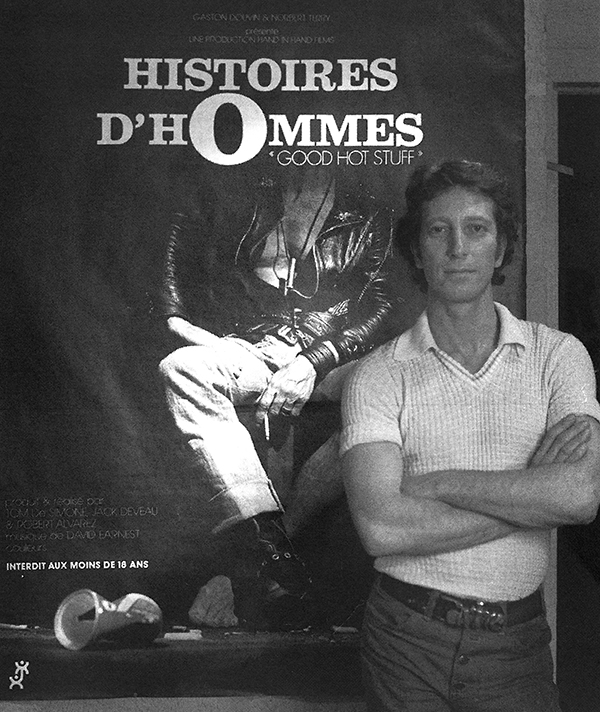

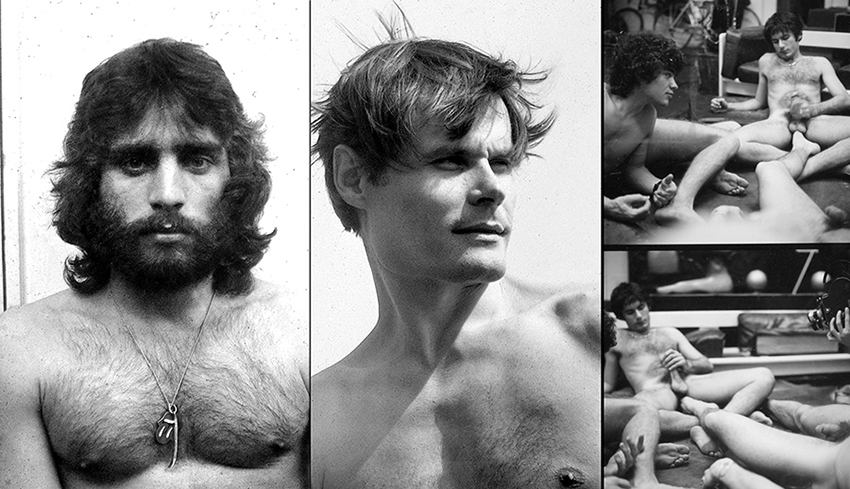

Robert Alvarez in front of French poster for Good Hot Stuff, 1975

Robert Alvarez in front of French poster for Good Hot Stuff, 1975

[Image Credit: Good Hot Stuff: The Life and Times of Gay Film Pioneer Jack Deveau]

Bijou: I am curious about some of your filmmaking influences and your experimental film background.

Alvarez: Well, I’ve always loved movies. And, in addition to that – this goes back to 1958, maybe – I started going to see some experimental films that were being shown in a little storefront place, and I got to know about Kenneth Anger and Gregory Markopoulos, for whom I worked. Not even worked – I assisted [Markopoulos], is more like it. And then I ended up being in one of his films. And then there was Warhol, but Warhol didn’t really influence me that much. I wasn't a great fan of his movies, but I did follow certain ones. Chelsea Girls is one of his early ones that I more or less liked, because it was so outrageous. The most influential [experimental filmmakers] for me were the ones that I just mentioned.

In addition to that, one of the first things that I came to New York to do was to become a dancer, because I started studying in Florida when I was about 18 or 19 and decided that New York was the only place that would be smart for me to go to. So I moved here and I kept studying dance and going to auditions, and so forth. After a while, I wound up doing Summer Stock and then a touring company. I did it ‘til I was about twenty-five and then I just decided that I should not continue to pursue it, that I should do something else. And, of course, the thing that came up in my mind first was film. I worked for [the animator] Francis Lee while I was doing the experimental film part of my life. He worked with this thing called photo animation. And he also made some experimental films, as well as regular ones.

I started getting more into film and wound up working for another animation man who did commercials for NBC, and then from that I went onto NBC and became assistant editor to the supervising editor there, and after that I got my first editing job. And, in between, I did some other stuff and wound up doing the documentaries [Woodstock, An American Family] and working freelance for mostly – it was Channel 13; it’s now PBS - until 1971 or ‘72.

It was my partner who I convinced we should get into the business of making movies, which is a story in itself, but, anyway, we turned out our first film, which was Left-Handed, and it was very unlike any other gay films that I’d ever seen. I became more and more interested in how far we could push the envelope, you know. Wakefield Poole, a pretty good friend of mine, made Boys in the Sand prior to this and that was a big success. And so we decided we would do ours, and that’s when we did Left-Handed. And ours was quite different, of course. We tried to take it from a different gay slant than just porno, give it some kind of a plot and characters and motivations, and so forth, as well as some editing that I did that I think was somewhat experimental.

Bijou: Had you edited any pieces that were that experimental at that point in time, or were you kind of getting to develop some of those techniques in your editing style on Left-Handed?

Alvarez: I actually was influenced by… I never got over being a dancer, and I was interested in dance and choreography, and so forth. When I started editing, I began to feel that there were a lot of similarities in certain aspects of editing to choreographing, and became a real fan of Bob Fosse, among others. So I used a lot of their techniques, but I also used some other techniques that I learned back when I was seeing experimental films, that involved quick cutting and a lot of - especially in Markopoulos - a lot of very extended dissolves, and things, that were quite beautiful. And I used those things, myself, as well as my sense of rhythm and cutting to music, which I loved to do, because that really gave it movement; some emphasis, depending on the music that we used. And we had original music for Left-Handed that came from a friend of ours, a guy that was a sound mixer, who had a small band. He composed some music for us.

Bijou: Yes, those are wonderful pieces.

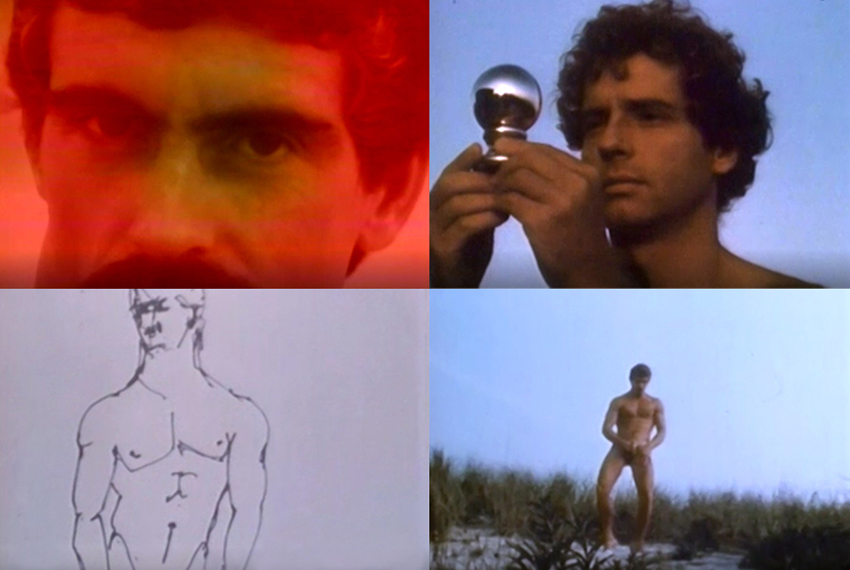

Images from Left-Handed, 1972 (DVD | Streaming)

Images from Left-Handed, 1972 (DVD | Streaming)

Alvarez: Anyway, I really enjoyed it, because I was doing it like I wanted to do it, and I was given a free hand to do whatever I did. So that more or less gives you an idea of how I got started, and where.

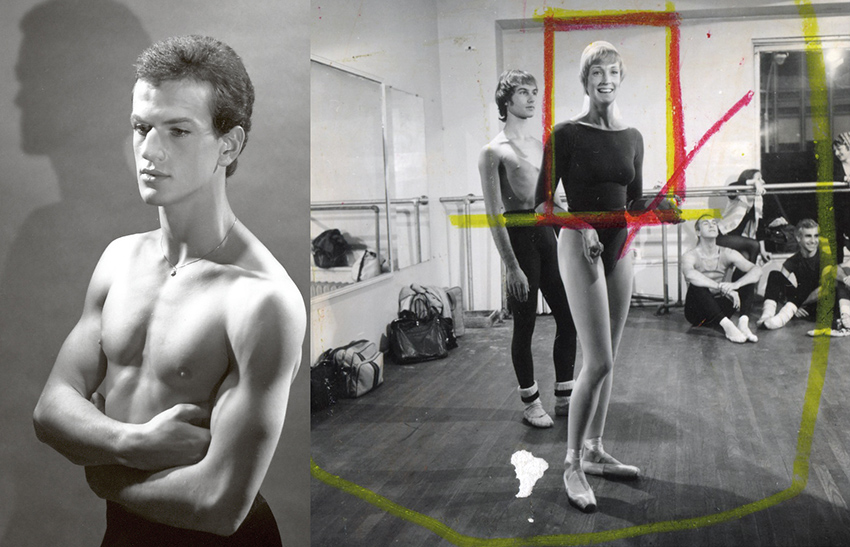

Bijou: I didn’t realize you came from a dance background, also. I know some other people involved [in making gay porn in '70s NYC] were from that background. Did you get connected to anybody through the realm of dance that wound up working with you?

Alvarez: Well, I had known Wakefield slightly back in Florida, because he was in a ballet company and I was in a different one. We met at some kind of convention. We got to know each other and we were sort of, not buddies, but… We were in two different locations in Florida. But when I came to New York, I saw that he was dancing, and, also, he did some choreography. So I got to know him pretty well.

Bijou: Do some of the people involved in Ballet Down the Highway come from those connections?

Alvarez: They did, but they weren’t friends or anything. They were people that we cast, who were dancers, to be in the ballet scene, as well as the lead in the movie, who was a Dutch young man [Henk Van Dijk] who came with a choreographer that we got to know from the Netherlands ballet, and became rather close friends with after this lover of his appeared in our film. Anyway, we got this young man, who was studying dance, and he was not a great dancer, but through editing and so forth, I made him look better. (laughs) You know?

Bijou: (laughs) It does look good.

Alvarez: He always remarked on that, you know, how I made it look like he could really dance. Other than that, the other people that were supposedly in this company he was dancing for were cast from, I guess, one of our casting calls. We put out casting calls for some of our films, like in Show Business [the newspaper].

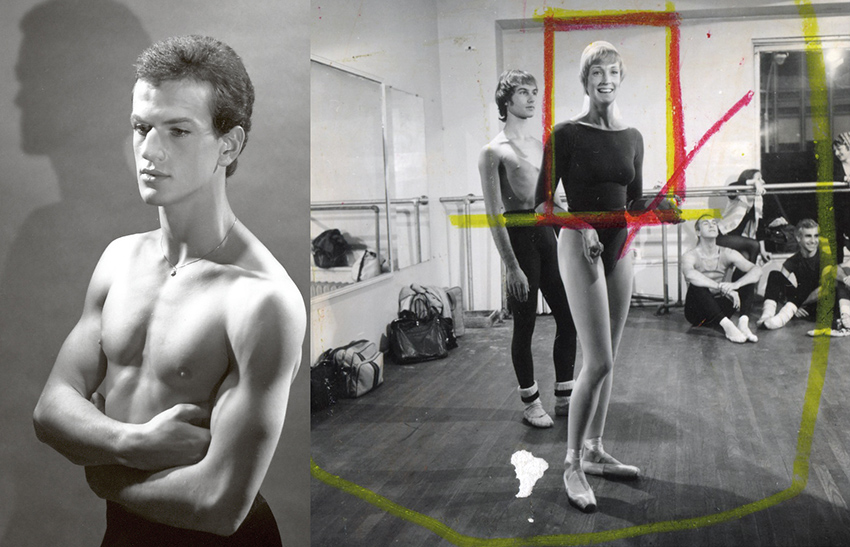

Henk Van Dijk (left) and other dancers & cast members (right) in Ballet down the Highway, 1975 (DVD | Streaming); clips from the film

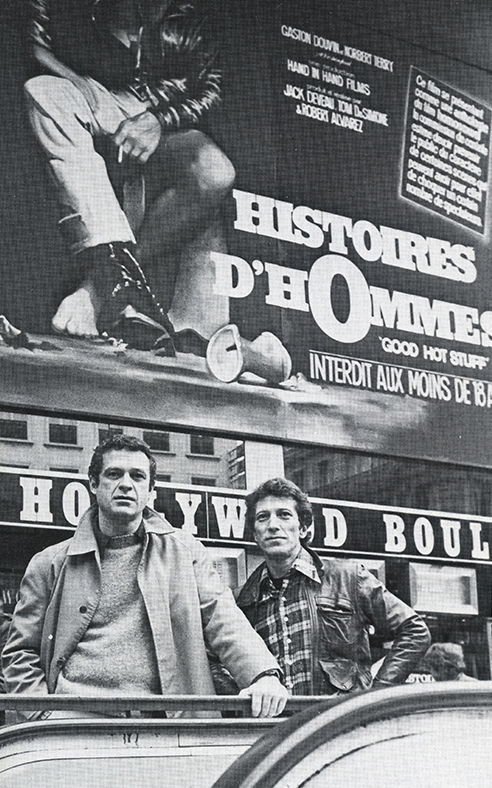

Bijou: Is that how you found most of your performers - casting calls? I noticed, with Hand in Hand's films, there’s some crossover between people you have in the crew and the cast, and some people that I don’t see in any other [adult] films. I was curious where the Left-Handed cast came from or if you knew some of them from social circles, as well.

Alvarez: The Left-Handed cast, I’m not sure, because I wasn’t involved in the casting, directly. That was Jack Deveau, who was, of course, my partner, and the guy who was primarily the producer/director - you know, the whole shebang. He used to put out casting calls. And, I think, we knew the guy who played the lead. We knew both of them. And so they agreed to be in it. And then we had an orgy scene at the end that was a lot of other people that we weren’t particularly friends with but somehow got to be in this, our first film. And I’m not sure whether they were cast directly, or they were cast through friends, or something. But that’s more or less how that happened.

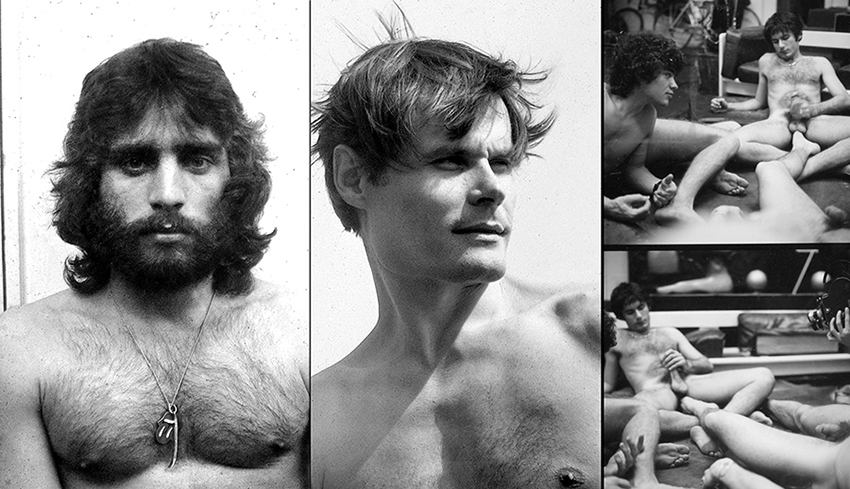

Ray Frank & Robert Rikas, the leads in Left-Handed, and orgy cast

Ray Frank & Robert Rikas, the leads in Left-Handed, and orgy cast

Bijou: How did you and Jack meet? I don't think I know that.

Alvarez: Oh… That’s a kind of a story in itself. We met several years before. I met him, actually, at a performance of an opera by Gian Carlo Menotti called The Saint of Bleecker Street. It was written up in the papers as being a really good production, and blah blah blah. I had a friend who wanted to be an opera singer, and I think he told me about it and said, “Do you want to go see it?” And I said, “Yes. I definitely want to go see it.” Because I knew who Gian Carlo Menotti was and I’d heard some of his other work and always liked it. But anyway, I went to that and, during intermission, this young man came up to me, you know? And we started talking, and so on, and so on, and so forth. And I had a feeling that we were… we were evaluating each other. (laughs) Also, it turns out that his mother was part of the orchestra. She played the viola. During that intermission, she came out, and he said, “Tell me your name really quick, because there comes my mother and I want to introduce you.” (laughs) So we met and… She’s a wonderful lady. Just a wonderful, wonderful person. Anyway, I immediately got interested in knowing more about him. He invited me to go out with him after the opera, which I did. And that was the beginning, you know? And, little by little, we became more and more involved until we decided to live together. It was good. We had a sort of an open relationship - not completely open, but rather. And so there were a lot of other sexual experiences that I had that were not with him, but were influenced by him. I’ll put it that way. (laughs) He was very interested in people that he’d meet off the street who were either hustling, trying to make a little money, or sailors, you know. He had a very great gift of gab, so he could charm anybody - and did. (laughs)

Bijou: Yeah. It sounds like everyone loved hanging out with him, from all the people I’ve spoken with about him.

Alvarez: Yeah, he was a lot of fun. He was a funny character.

So anyway, we had this relationship, never really committing to a long-term thing, but it kept going, kept going, kept going, and we ended up being together for twenty-one years. And at that point, he died, and so... It was a long, long relationship. And I loved him very, very much. And vice versa.

But I always thought it would be great if we could work together. Incidentally, another person that was greatly responsible for Jack getting the courage to get into this and actually direct people was [Rebel Without a Cause star] Sal Mineo, who became a friend of ours some years before.

Bijou: Yeah! I was so curious where you knew him from.

Alvarez: We met him in Madrid, and he was getting ready to shoot a film somewhere in Europe. I can’t remember the name of it. Anyway, we got to know each other, and while we were there, we went out together. And he was sort of… not just coming out, I guess, but he was definitely coming out. (laughs) And so he enjoyed being with us, and was always a good friend.

And then a little later, we got into the film business and decided to become our own distributors, because we didn’t trust any of the distributors. Everybody that had dealt with the distributors had been pretty much ripped off by having copies of their films made and sold, and all kinds of stuff that went on. We felt it was better if we could set up a business to distribute our own movies and not sell them, which a lot of other gay filmmakers were doing. Instead of selling them to make a quick buck, we’d keep the movies and then rent them out to the exhibitors and charge them a percentage of the gross. And, of course, they were never exactly honest, either, but we found ways to kind of get around that. When we showed our stuff in New York, we had somebody counting the number of patrons that would go into the theater, so we had an idea of about how much money we should be getting. But anyways, that’s a whole other area of the business. And, incidentally, that’s how we met [Bijou owner] Steve Toushin, because he started renting some of our films, and we liked him. He was always really very nice and very fair.

Bijou: I was wondering about Good Hot Stuff [Hand in Hand's documentary about their studio] showing in Paris. I read that that was the first gay porn film to show in France. I was curious about that trip over there and what that experience was like.

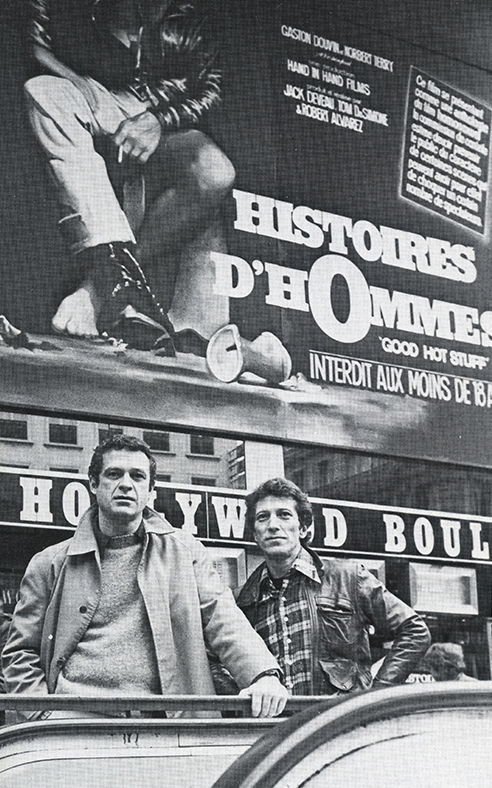

Jack Deveau & Bob Alvarez in front of French billboard for Good Hot Stuff (DVD | Streaming); excerpt from the film

Jack Deveau & Bob Alvarez in front of French billboard for Good Hot Stuff (DVD | Streaming); excerpt from the film

Alvarez: It wasn't the first film. It was the first American explicit gay film ever shown in France. We hooked up with a man named Norbert Terry in France who had apparently shot one or two movies that were in French. I always wanted for us to go there and be shown with subtitles and (laughs), you know, the whole thing. Because there’s a lot of narrative to Good Hot Stuff; Jack and some of our actors talked about being in the films, and so forth. We opened in Paris at two or three theaters. And they made a big deal out of promoting it. And, sure enough, we ended up outgrossing the [Robert Altman] movie Nashville, which was also playing there (laughs) - and Nashville is a classic film.

Bijou: (laughs) Yeah, that's amazing.

Alvarez: Jack and I had been to Paris a couple of times before, and we loved Paris... I still do. It’s a magical city and I love it. So we ended up, eventually after we made some more films, making a deal with a guy who was a producer in Paris, and contracted to make a movie in French and we would share the profits. It turned out to be a disaster, but we released the movie anyway.

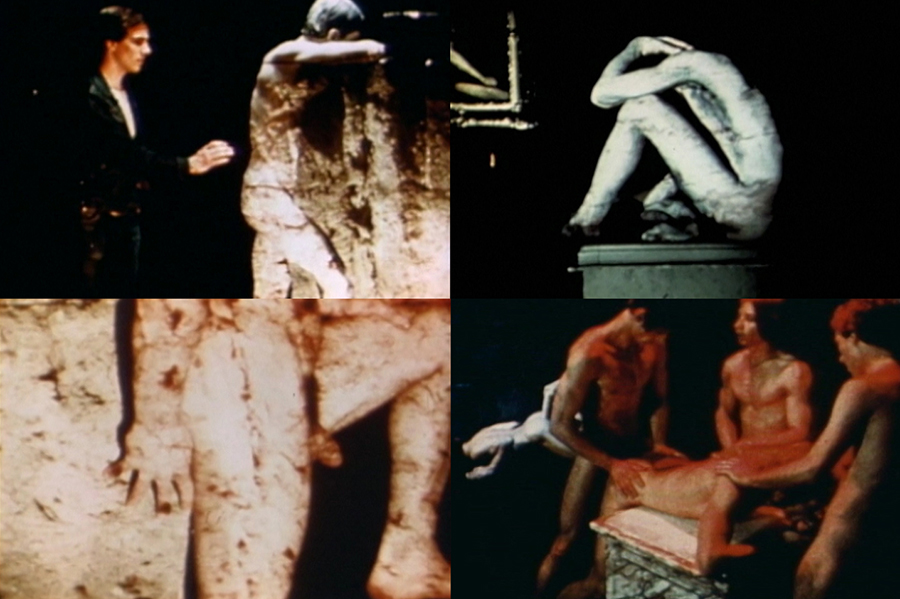

Bijou: Was that Le Musée, [also known as Strictly Forbidden]?

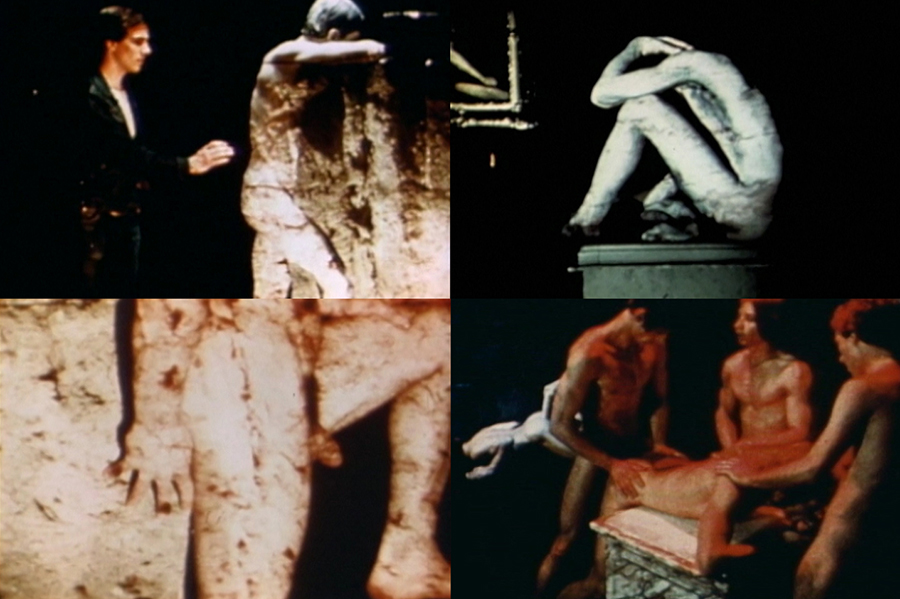

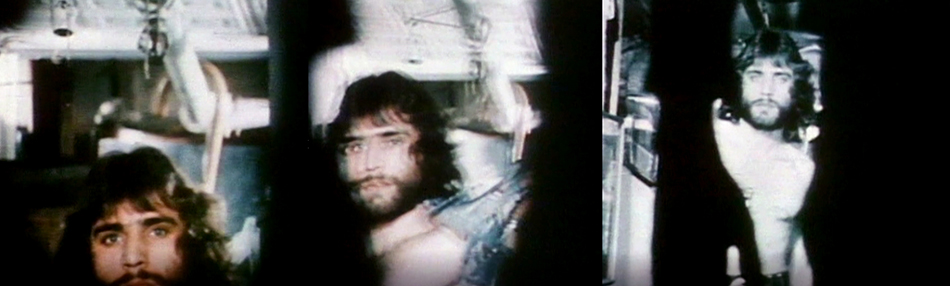

Images from Le Musée aka Strictly Forbidden, 1974 (DVD | Streaming)

Images from Le Musée aka Strictly Forbidden, 1974 (DVD | Streaming)

Alvarez: Le Musée, yeah. I had to end up using our work print, because they had confiscated our original negatives from the lab, so I had only the work print to work with.

Bijou: Oh wow, they confiscated it?

Alvarez: Yeah. They figured they had a legal right to do it, because we ran out, I guess. We didn’t continue working on the film. We left, and when we went to get our original negatives, found out that they had already been taken by the production company, and they weren't about to give it up.

Bijou: Wow.

Alvarez: Which is too bad, because it was really a beautiful film in many ways.

Bijou: Yeah, the footage is gorgeous from that film.

Alvarez: Yeah, the color footage is really good. And that’s only the work print, so you can imagine the original.

Bijou: Oh wow. I see, so the B&W is the work print?

Alvarez: Yeah, that’s all from the work print.

Bijou: Oh!

Alvarez: And I decided, from my experimental film days (laughs), “Hell, I’ll just mix them all up,” you know, and we’ll have B&W and color.

Bijou: I like that about it. I thought that was intentional. It felt intentional, watching it. (laughs)

Alvarez: That’s what I tried to do - make it look like it was intentional. I wasn’t happy with it, completely, because I knew what we could have had, but we didn’t want it to go to waste, so we released it. And made some money on it, you know.

Bijou: Yeah, I still think it’s a great one, but that would be sad knowing that you lost a good chunk of footage. What was your philosophy on making the Hand in Hand films at the time?

Alvarez: Well, almost all of them were shot in New York, and we dealt with New York situations and stories. I mean, Left-Handed is certainly that. And several others we did were about typical New York scenes. Some of our slighter stories had New York characters in them, and we used New York as a kind of a backdrop for everything. So we decided our films would have that element, as well as kind of a freewheeling style where we made it seem like being gay was a normal thing, long before (laughs), long before [many gay rights advancements]. We were just assuming that our characters all were gay and that’s how they talked, as normal people would talk.

Bijou: That’s true, that is kind of distinctive about your films - now that you said that - versus some other studios. In Hand in Hand's films, most of the people are already out and it’s set within gay life and that’s not, like, a huge ordeal with it.

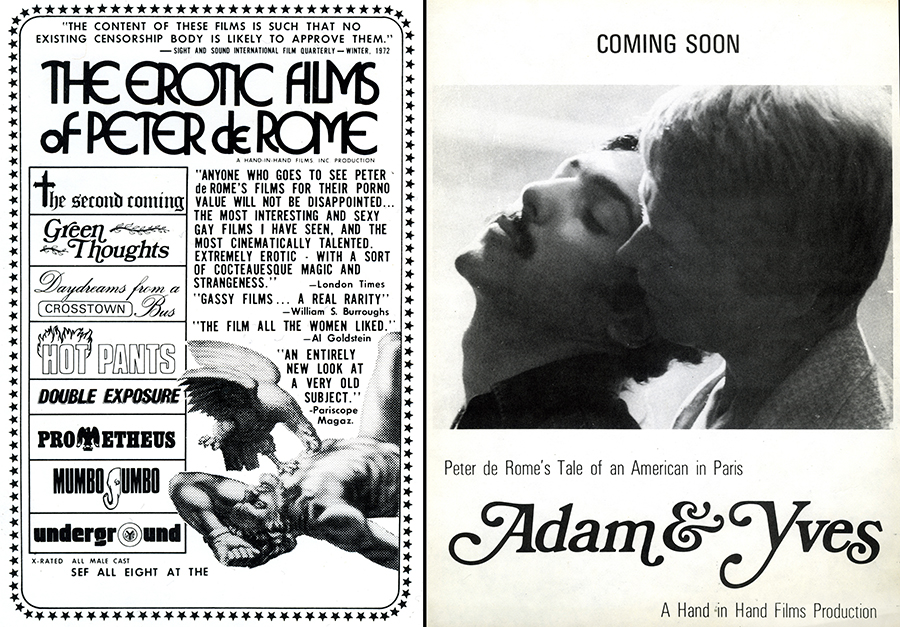

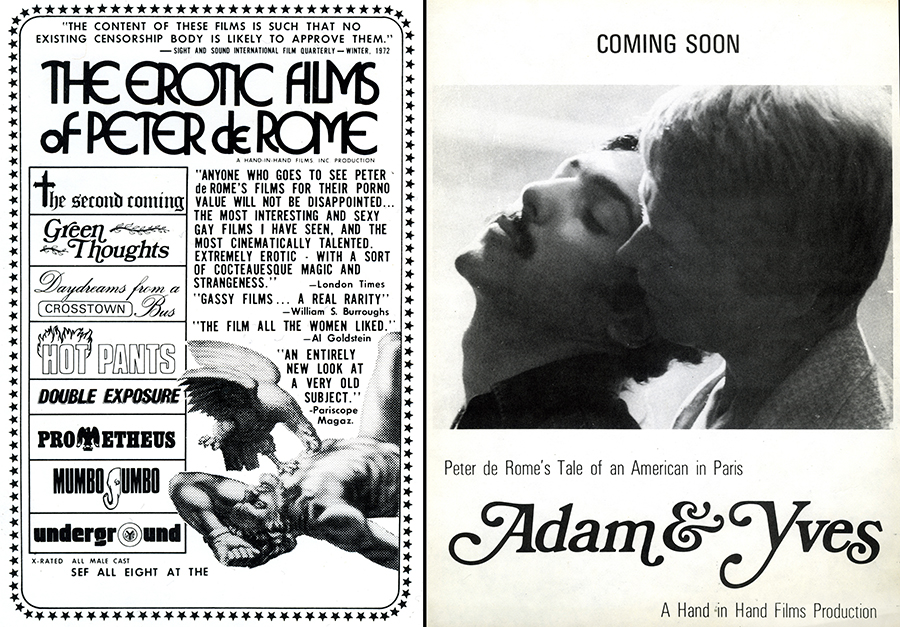

Alvarez: Yeah. And another film that we did early was… Well, we worked with this guy Peter de Rome on his first feature-length film. ‘Cause he had done some short films on 8mm. We ended up blowing up a lot of them to 16mm, and then adding a couple of his [other] short movies, and making a movie, after that, called Adam & Yves, which took place in Paris.

Posters for The Erotic Films of Peter de Rome 1972, (DVD | Streaming) and Adam & Yves 1974, (DVD | Streaming)

Posters for The Erotic Films of Peter de Rome 1972, (DVD | Streaming) and Adam & Yves 1974, (DVD | Streaming)

Jack Deveau and Peter de Rome filming Adam & Yves; audio and set photos montage

Alvarez: Another chance to go to Paris; I didn’t go to, but Jack did. We made the film that Peter de Rome directed. Well, Jack actually directed it more than he did, but…

Bijou: Oh really?

Alvarez: But we gave him the credit, because it was his idea, and his concept and the whole thing about shooting some of it in Paris.

After Adam & Yves was released, we started working on a film which was a little more intricate… a lot more intricate, actually (laughs), called Drive. And I did a lot of quick cutting and switching from one scene to another, like in the middle of a sex scene; kind of making a comment about what was coming up, you know, sort of like a prequel to what was going to happen.

Bijou: Yeah, I love the edits in that movie.

Alvarez: And it took place in this decadent disco that was run by the character named Arachne, whose goal in life was to rid all men of their sex drive. But she would do it by castrating them, up to the point where she found out that there was this drug being developed... This was funny, too, because this was long before Viagra or any of that stuff. But there was a drug being developed that would kill the instinct or the desire to have sex. So she wouldn’t have to be mutilating people anymore. (laughs) So her goal was to go out and get this drug and the scientist. She was an evil character. But as far as the movie goes and my involvement in it, I was very taken by this and I loved the idea that some of it took place in a disco. And there was a scene that was kind of a tribute or take off on Marlene Dietrich’s gorilla suit sequence in [Blonde Venus]. But we did our version of that with the character Arachne, who was in drag, of course, and I loved it. I think it really works well. And that’s one of the scenes where I cut to the disco. And we had original music for it. Now, I did my best to cut to the music, and then I intercut with the sex between the detective and his partner. So we go back and forth, back and forth, back and forth, until the scene at the disco became a climax when the Arachne character takes off the gorilla head and out she comes. And so that was the end [of the scene], and that was in vivid color. And at the same time, the couple was climaxing in their scene, and so the two climaxes kind of coalesced together.

Bijou: It's a great sequence.

Christopher Rage as Arachne, after emerging from the gorilla suit in Drive, 1974 (DVD | Streaming); Drive's original theme song by David Earnest

Alvarez: That’s what I mean about our films. I mean, there was so much… Not to make art, necessarily, but to make something that would be contemporary, of the day, and also would get us… We always had the goal, really, to get into regular movies - mass market movies - eventually, and this was sort of going to be our training ground. And, for a while, it looked like we could do it. I know Wakefield had the same desire and almost made it. But the whole business changed so quickly, and it became corrupted, and more of a “quick buck” kind of thing, and so forth. There were exceptions. There were a few filmmakers that were rather important at that time, and one of them was a guy by the name of Tom DeSimone, who ended up working with us on a couple of movies.

Bijou: Right, he shot a couple of them, didn't he?

Alvarez: Oh, he shot many films. That’s a whole other story. It’s in the book [Good Hot Stuff: The Life and Times of Gay Film Pioneer Jack Deveau], in the chapter on Tom DeSimone. Anyway, we liked him, because his movies - the movies he made, himself - were more substantial, and often had plots, and so forth. There were a few people like that. Another one was Fred Halsted who, in L.A. Plays Itself, used a rather - not only shocking - sequence, but also some underground film tactics.

Anyway, I was talking about Drive and how that was a departure from everything.

Bijou: Yeah! That’s the first really kind of elaborate effects piece that you did, right?

Alvarez: Yeah, exactly. I took some of the disco stuff to an optical house and had them do several things to make it more unusual. You know? I incorporated a lot of stuff like that in all our films, if possible.

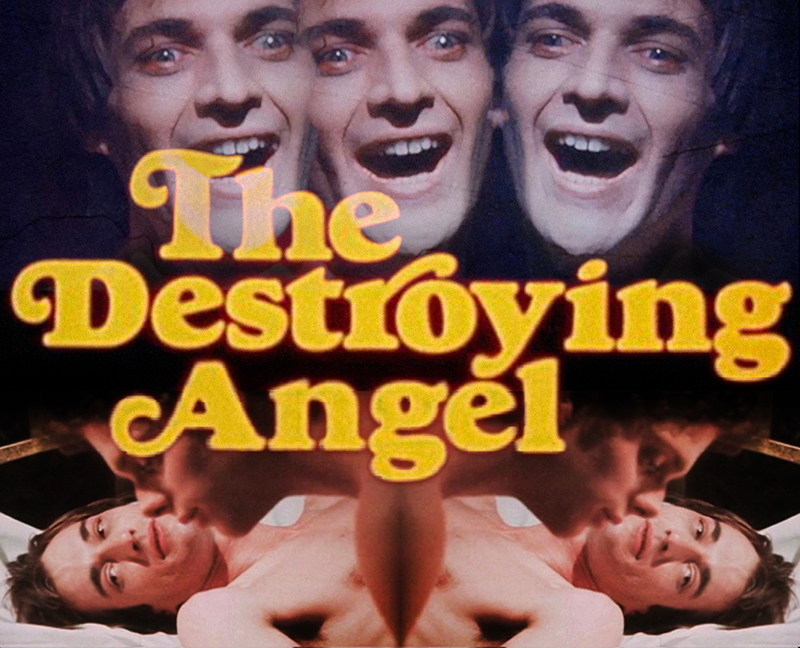

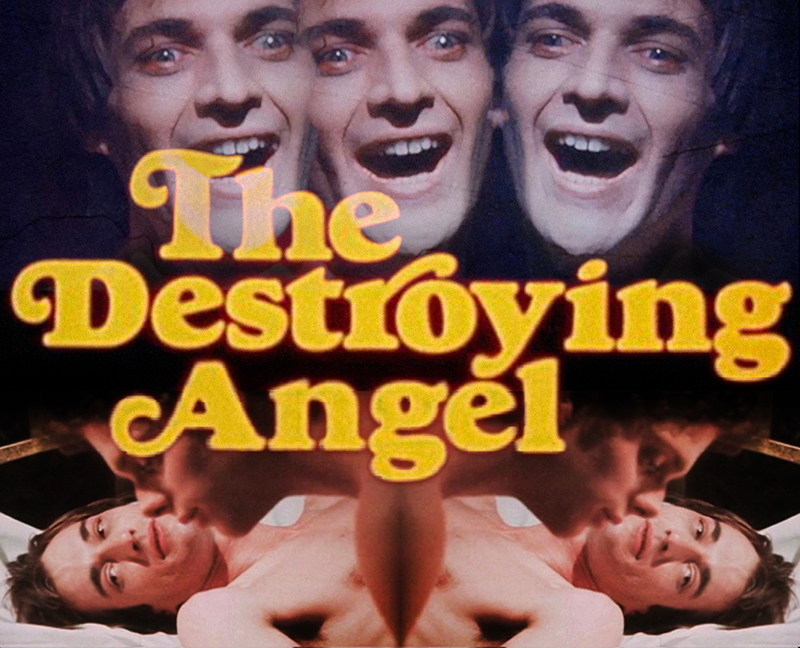

Bijou: Right. Destroying Angel has couple of those great sequences, too.

Alvarez: Right, Destroying Angel, especially.

Bijou: I love that one.

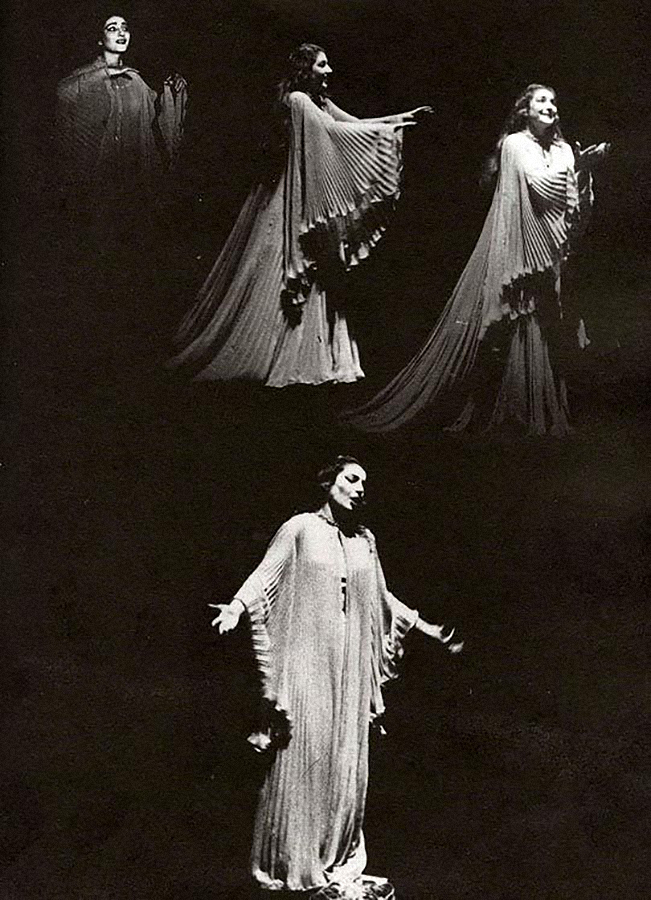

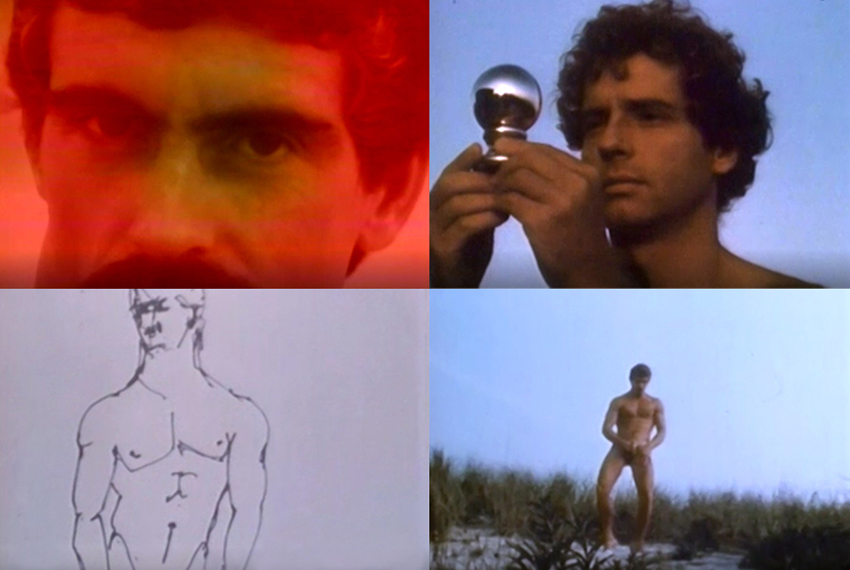

Images from Peter de Rome's The Destroying Angel, 1976 (DVD | Streaming); excerpts from the film

Alvarez: Yeah. And there’s one called Fire Island Fever, which has a sequence where one of the characters accidentally takes a tab of acid and we kind of see what he’s seeing through his eyes as he is high, which is a fantasy sex scene with what turns out to be one of the characters that he meets at the end of the film. Anyway, I tried as much as possible to incorporate some more daring kind of editing. You know, make our films look different. And they did. (laughs) For the most part, they did.

Bijou: Yeah, they did!

Fantasy sequence from Fire Island Fever, 1979 (DVD | Streaming)

Fantasy sequence from Fire Island Fever, 1979 (DVD | Streaming)

Bijou: Oh, I wanted to ask you about Kees Chapman.

Alvarez: He was also, I think, from a Dutch background. But he was an American; I think he was born here in the States. His lover had been one of our actors early on. [His lover] was actually in Drive. He played the scientist. He had long blond hair. For the movies, he was [named] Mark Woodward; to us, he was his real name, Sydney Soons. And he became an employee of ours, and was helping Jack with keeping track of the finances and getting the movies sent out to the exhibitors, and all that.

Mark Woodward aka Sydney Soons hosting Good Hot Stuff and slating for A Night at the Adonis, 1978 (DVD | Streaming)

Mark Woodward aka Sydney Soons hosting Good Hot Stuff and slating for A Night at the Adonis, 1978 (DVD | Streaming)

Alvarez: After a while, he and Kees ended up breaking up, and then Kees kind of took over his job, and became even more of a necessary part of Hand in Hand Films. And he also ended up doing some camerawork for Jack, as well as directing, and so forth.

In fact, he shot the sequence I directed in In Heat, which was shot in a dance studio. It was guys taking a ballet class, and then the teacher takes a break, and during that time, the boys get together and have sex. And eventually, the teacher comes back and he joins the crowd. (laughs) So that was one small segment that I directed, because I’d always wanted to, but I didn’t want to impose on Jack’s ideas, you know, because he had plenty of ideas.

Dance studio segment directed by Robert Alvarez in the Hand in Hand shorts collection In Heat (DVD | Streaming)

Dance studio segment directed by Robert Alvarez in the Hand in Hand shorts collection In Heat (DVD | Streaming)

Alvarez: In fact, Kees and I tried to make a full film, with Kees directing, after Jack died, but it turned out that I couldn’t use the footage; it was too dark and just a mess. And I’ve always thought I should take that footage again and look at it again with today’s technology, you know?

Bijou: Oh, you should. I bet it could be enhanced a bit, yeah. That would be interesting. What was the premise?

Alvarez: I’m not too sure, except I know that it had the lead character going to Fire Island and having several encounters there. And finally, at the end, I think he gets back with his lover that he had at the beginning of the movie. It’s been a long time since I’ve looked at it.

Bijou: I bet it could be brightened.

Alvarez: Yeah. I think with today’s video technology, especially, a lot of things can be certainly improved. Steven’s done that already. I’m very pleased with the way he has kept our movies up to date.

Bijou: Oh, I'm glad.

Alvarez: Oh, let me finish with Kees. Like I said, he became part of our group that ended up being Jack, Kees, and myself, who were the principal people. We had another partner for a while named Jaap Penraat. But that ended at some point and… Not too happily, but it ended.

And that’s when Kees became interested in working for us and kind of took over Jaap’s position, and started working with Jack directly. He was a terrific guy. And I was very surprised when he died of AIDS because… He must have gotten it from his lover, Sydney, because Sydney also got it and also passed away. And, a year or two later, Kees became ill and he died.

So that left it just up to me, and that’s where I finally decided - after making that little film, which was kind of satisfying for me - that it was time to get out of the business. That’s when I started looking for people that might be interested in buying the business, buying all the material, which turned out to be Steve. And I’m glad it was, because he’s been the most trustful of the ones that I talked to about it. There were other people interested, but I knew what would happen. We wouldn’t be who we are today if it had gone to somebody else and they copied our films badly and, you know. It would have been awful. So I’m glad Steve had some real interest in keeping it as a sort of a record of what was happening in the time when they were made, and so forth, which was one of the things Jack…

Speaking of the philosophy, you know, he said that these films were like literature and that if we kept them - you know, rather than sell them - we would end up eventually having them seen over and over and over again and be a representation of what it was like in the days that we shot them, you know? Because most of them were contemporary stories of people at that time. So that’s kind of what his philosophy was. He would make films and try to incorporate things that were relevant to the time that we were shooting in.

Bijou: Yeah, that was probably a conscious effort from the start, even from Left-Handed?

Alvarez: Yeah. It’s funny. After making Left-Handed, and then making a few others, I kind of became a little bit… It wasn’t embarrassed exactly, but… Left-Handed is, no question about, it a crude film. We didn’t shoot in sync sound, we had to dub in the voices, and so forth, and we did it as best we could. And then, Left-Handed always bothered me, because, to me, it wasn’t professional. And looking back at it now, I find I like it very much, you know? (laughs) I like what we were doing.

Bijou: Yeah, I think it's great.

Alvarez: And the fact that it was different. It was different than any other gay sex film that was ever made.

Bijou: Yeah, it is! It does stand out. Even the non-sync sound does something really interesting in it. Its style feels really different, even from your other work.

Alvarez: Yeah, yeah. To me, now, the dubbing almost becomes like a narration, you know? Like it’s almost purposefully done that way (laughs), you know, after the fact. But anyway, I ended up really liking Left-Handed a lot, because it sort of set the mood, also, of my type of film editing. And a lot of the techniques I used in Left-Handed, I used later on in other films that we made, so it kind of was our benchmark movie, being our first.

Bijou: That’s interesting you mentioned developing some techniques there, because in terms of developing cutting hardcore sequences, since the genre was pretty new in the era, were you sort of figuring that out from scratch or… I mean, you’d seen some other [porn] films, but… What was that like developing how to cut and how to pace those sequences?

Alvarez: Well, for one thing, our films, sometimes they got criticized because they weren’t explicit enough, whereas some films are almost like a medical study.

Bijou: Yes. (laughs) Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Alvarez: Ours were more like – at least I felt and Jack felt – to capture the sensuality of the sex or the dynamics of a sex scene, and whatever shot said that the best is the shot that we used. So we didn’t go in for, like, where you can see every pubic hair, you know? (laughs)

Bijou: (laughs) Yeah. Right. Because that B&W sex scene from Left-Handed is, I think, very beautiful and erotic, but it’s far from being like a medical, durational kind of sex scene.

Alvarez: Yeah. And that B&W sequence in that section, Jack did on purpose B&W, because he said, “We’re going to do like The Wizard of Oz, only backwards.” (laughs) In The Wizard of Oz, it’s in B&W until Dorothy goes through the door, and goes into Oz, and it becomes Technicolor. [And in Left-Handed], when it becomes a dream sequence, it turns into B&W film. And that’s how that came about. And with things like that, you know… I mean, we did that before anybody else [in sex films] did that. Maybe some people followed us, you know, and did the same sort of thing, but… But my cutting, especially, I really loved the idea of creating a piece, a sex scene that had some rhythm to it and some sense of movies, of real movies, you know?

Bijou: Oh yeah, that’s a good distinction, because the sex scenes do feel cinematic in your films.

Left-Handed color to B&W shift

Left-Handed color to B&W shift

Alvarez: Yeah. So that’s pretty much the story of Hand in Hand Films. There’s a lot more. If you look at the book, you’ll see that there is a lot more. (laughs)

Bijou: Oh yes, there is. It's a fantastic read. I’m so happy you all put that together.

Alvarez: The book was written by a German guy [Marco Siedelmann] that I met and got to know at a festival where our films were shown, and he said, “I want to do a book on Jack Deveau.” So I said, “Great!” And he said, “And it should have pictures,” and I thought, well, I have some pictures. I mean, Steve has most of them, but I kept a few for myself. You know, things that were duplicates, and so forth. And so, with that, I was able to help him get this book out.

Book cover - Good Hot Stuff: The Life and Times of Gay Film Pioneer Jack Deveau

Book cover - Good Hot Stuff: The Life and Times of Gay Film Pioneer Jack Deveau

Thank you to Robert Alvarez for taking the time to talk to us and share stories. For much more information about Hand in Hand Films and a more extensive interview with Alvarez, please check out Good Hot Stuff: The Life and Times of Gay Film Pioneer Jack Deveau.

Bijou is very proud to present Hand in Hand's full film catalog! You can watch their movies on DVD and Streaming.

Further Reading, Listening & Viewing for more information on Hand in Hand Films:

Excerpt from the Hand in Hand Films documentary Good Hot Stuff (1975) on Vimeo and more Hand in Hand clips on our Vimeo and YouTube channels

Bijou Blog - Jack Deveau: Vintage Gay Porn Director Profile

Interview with Tom DeSimone (Part 1 and Part 2)

Ask Any Buddy podcast episodes on movies produced and/or distributed by Hand in Hand Films: Good Hot Stuff, Drive, The Night Before, Adam and Yves, The Destroying Angel, Rough Trades, Fire Island Fever, American Cream, Catching Up, The Idol

Join our Email List

Join our Email List Like Us on Facebook

Like Us on Facebook Instagram

Instagram Youtube

Youtube Follow Us on Twitter

Follow Us on Twitter Follow us on Pinterest

Follow us on Pinterest